It was truly a December surprise. On Dec. 22, the FCC blacklisted all new foreign-made drones and critical components over concerns that such gear poses “an unacceptable risk” to U.S. national security.

Then came a partial walkback, when last week the FCC carved out exemptions for drones on the Pentagon’s Blue UAS Cleared List and those meeting a 65% domestic parts threshold — a reprieve for allied manufacturers through the end of 2026. The Commerce Department also quietly withdrew its own proposed restrictions, which would have been more draconian, potentially grounding existing fleets rather than just blocking new imports.

DJI got no such relief. The world’s dominant drone manufacturer (with ~80% share in the U.S.) is now functionally iced out of the American market. Its existing models can still be sold and flown, but the pipeline for new DJI products has closed.

The security concerns are legitimate and longstanding, having been articulated for the better part of a decade. For instance, DJI hardware can transmit telemetry to servers accessible by Beijing, and >80% of America’s public safety programs flew DJI drones as recently as 2021. Reducing that exposure makes sense.

But what fills the gap, and for whom?

American drone companies are thriving in delivery and defense. Zipline is closing in on 2M autonomous deliveries with zero safety incidents, is growing insanely quick in the U.S. (+15% week over week), and recently secured $150M to triple its Africa network. Wing, Alphabet’s drone delivery unit, and Walmart aim to scale to 270 locations by next year, which would allow them to serve 10% of the U.S. population by 2027. The Pentagon’s Drone Dominance Program is procuring 340,000 tactical drones over the next two years, with a range of startups, neo-primes, and existing manufacturers competing for contracts.

The consumer and commercial market is a different story. Real estate photographers, prosumers, farmers, surveyors, and filmmakers — the operators who made DJI’s Mavic ubiquitous — face a market with no American substitute at a comparable price. A Pilot Institute survey found that 43% of drone operators expect the ban to have “extremely negative or potentially business-ending impact.”

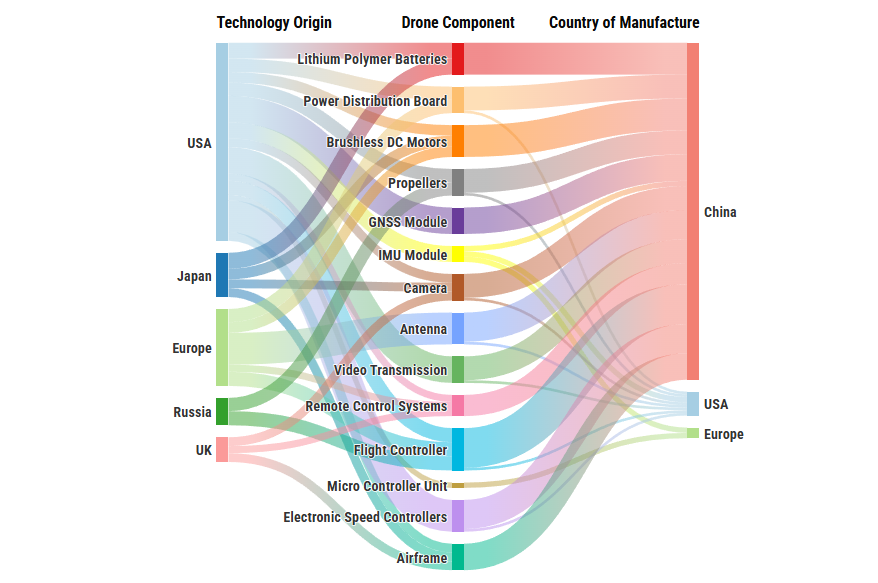

The U.S. and its Allies invented nearly every component in a modern drone: lithium polymer batteries, brushless DC motors, flight controllers, GPS modules, IMU sensors, sintered neodymium magnets, etc. Today, though, and you already know what’s coming next, we manufacture almost none at scale.

When Beijing sanctioned Skydio last October, the company couldn’t source batteries for months and was forced to ration customers to one per drone. CEO Adam Bry called it “a clarifying moment.”

The U.S. has had plenty of clarifying moments like this up and down the supply chain in recent years. We are investing heavily in reindustrialization and onshoring supply chains for systems like drones. It’s not an overnight process; and blind spots or near-total dependencies for certain components remain.

Still, there’s an opening here…

…one that hasn’t existed since 2016. That year, DJI’s dominance became clear as it crushed the American competition. The company’s combination of genuinely innovative design, rapid iteration, low prices, state support, and Shenzhen’s unparalleled supply chain efficiency has made head-to-head hardware competition nearly impossible. Those remaining from the consumer and commercial drone wars of the 2010s largely survived by pivoting to software or protected markets.

A decade later, the door is wide open again. Supportive industrial policy has changed the calculus for building stateside, with demand signals across government, enterprise, and consumer segments. Domestic magnet production is scaling and new battery plants are coming online. A company that cracks a key component, or the full system at consumer/commercial price points, with a domestic or allied supply chain, now has a real shot at a multi-$B market.

The component problem is solvable, but demands capital, time, and manufacturing capacity that will not materialize overnight. And while ripping off the bandaid hurts, depending on a single foreign supplier was never a stable equilibrium.

If you’re working on something in this space, get in touch! We’d love to hear more.