Introduction

Foreword

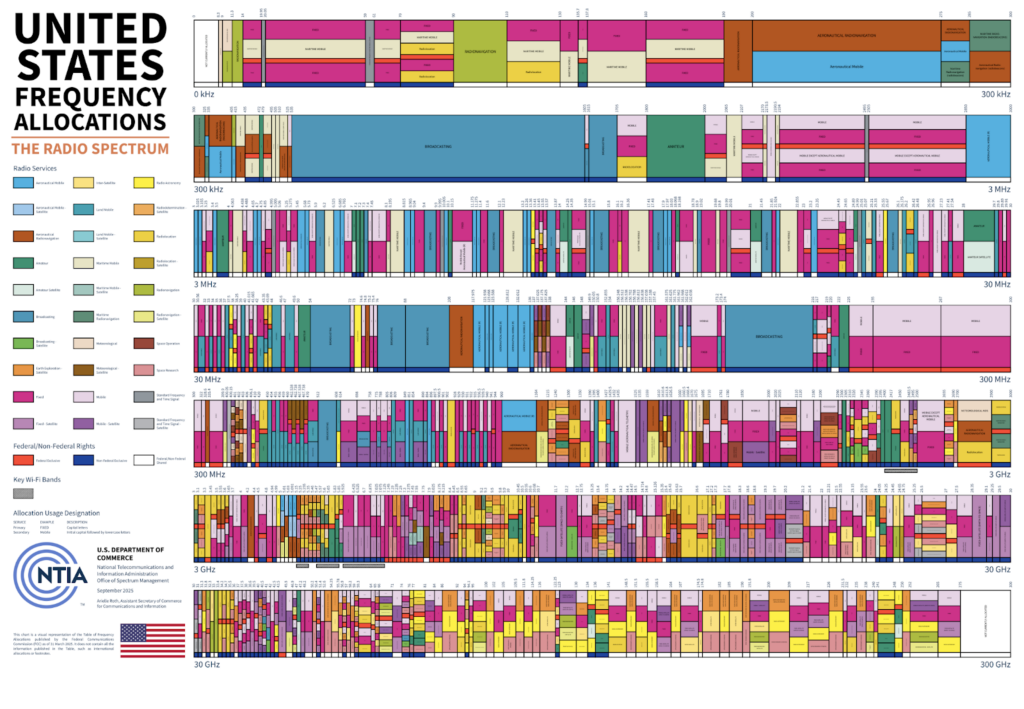

Most Americans have no reason to think about the electromagnetic spectrum. It is invisible, silent, and — until something goes wrong — effectively unnoticed. Yet spectrum is the medium that carries everything the country depends on: aircraft navigation, wireless broadband, satellite links, weather radar, GPS, emergency services, and the command-and-control backbone of national defense. Because our airwaves are out of sight, out of mind, few grasp just how finite they really are. That there are hard physical limits. That we live inside them without seeing them, and only notice the walls when we’re about to crash into them. This is the story of how America is losing control of its own atmosphere, and what we can do to win it back.

The $81B Near-Miss That Almost Grounded A Nation

It was December 2021. The wireless industry, led by Verizon and AT&T, was preparing to light up the C-band after securing the rights in the highest-grossing spectrum auction in history earlier that year. The carriers had plunked down a staggering $81B in bids for the 3.7–3.98 GHz band – the “beachfront property” of wireless spectrum where capacity, coverage, and propagation optimally converge. This was the specific asset that could make fifth-generation cellular networking technology (5G) really shine. The carriers secured their licenses, deployed their infrastructure, and prepared to flip the switch on the next generation of American connectivity. All told, the true cost was closer to $94B when including the clearing and incentive payments required to vacate the incumbent satellite operators.

Then, all hell broke loose.

On Monday, Jan. 17, 2022, America’s largest airlines wrote the White House with a warning: if 5G deployed on Wednesday as planned, it would trigger “catastrophic” disruptions to air service and ground flights all over the country. You see, weeks before, the FAA had escalated the standoff by issuing airworthiness directives claiming that 5G signals at 3.7–3.98 GHz would interfere with aircraft radio altimeters. These instruments, which pilots use to land safely in low-visibility conditions, were operating at 4.2–4.4 GHz.

Though there was a sizable 220 MHz “guard band” between the two – massive by valid technical standards, and twice what they generally require – the FAA wasn’t sure that it was sufficient for safe operation of altimeters (some designed in the 1970s.) So, the agency effectively threatened to ground planes in low-visibility conditions if 5G was active nearby.

The White House scrambled to broker an eleventh-hour truce. Verizon and AT&T voluntarily agreed to reduce power around 50 of the nation’s most popular airports for six months, which bought time for the aviation industry to retrofit equipment. Crisis averted, but just barely.

What the hell had happened?

The underlying issue was regulatory in nature. Two federal agencies, the FCC and the FAA, had been using incompatible interference models without talking to each other. The FCC had approved the auction and deployment, while the FAA used decades-old safety standards that assumed altimeters had zero filtering capability – effectively, that a radar altimeter designed in the disco era would be confused by a cell tower operating hundreds of megahertz away. This fiasco, which we’ll call C-band-gate, was not the first time the structural dysfunction of the nation’s bifurcated spectrum management system had come to a head. It would not be the last.

This is the inevitable result of running a 21st-century economy on a 20th-century regulatory stack. The architecture for managing American spectrum was revolutionary when it was designed — in 1934 — but it is structurally incapable of handling the velocity of modern warfare or the volume of the digital economy. We are effectively trying to route the entire internet through a switchboard operator. In this Antimemo, we will dissect that failure. We will walk through the immutable laws of physics that govern the airwaves, name the bureaucratic “original sin” that has paralyzed our government, and expose the false choice between national security and economic growth. The U.S. is currently drifting toward a future on “Spectrum Island.” Below, we lay out the plan to turn the ship around.

Section 001

The Laws of Electromagnetism

Think of spectrum not as a uniform asset, but a gradient of utility. Value is created and constrained by the physical characteristics of any given frequency. Every wireless system, from a garage-door opener to a missile-tracking radar, operates under the same immutable laws. These laws of physics do not care much for your agency charters, lobbyist inputs, or congressional mandates. Below, we’ll lay out the key principles. (If you do not care to get into physics, or this is pedantic for you, jump to the next section.)

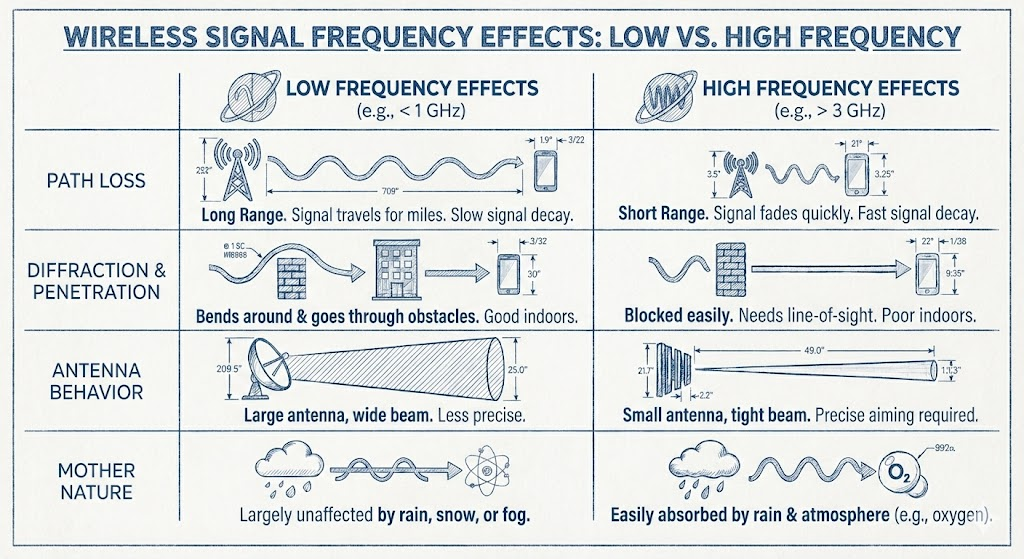

- Path Loss (The Distance Penalty): As a signal travels, it decays. This generally follows an inverse-square law: double the distance → lose 75% of the power. Crucially, higher frequencies decay faster than lower ones. At 700 MHz, a signal travels miles with modest power. At 28 GHz, it collapses in a few hundred meters unless focused by high-gain antennas. This is the first primary constraint: range costs power, and higher frequency costs exponentially more.

- Propagation (Bending vs. Breaking): Low-frequency waves bend; high-frequency ones break. Below 1 GHz, radio signals can diffract around buildings, terrain, and the curvature of the Earth. Above ~3 GHz, they begin behaving like light: they require a clear line of sight, and their ability to penetrate concrete, foliage, or even heavy rain drops off precipitously. This is why low-band spectrum forms the “coverage layer” of national networks, and why mid-band sits at the frontier: just high enough to carry data, just low enough to cross the city.

- Aperture (Size vs. Precision): Every antenna is a trade-off between physical size and beam precision. Lower frequencies require larger apertures to form directional beams. As frequency increases, you can steer power more tightly with smaller hardware. This makes Ka-band satcom and X-band radar possible, enabling small antennas, tight beams, and efficient links. But with narrower beams comes complexity — you have to know exactly where to point, and when.

- Mother Nature (The Weather Wall): As frequency increases, the atmosphere stops being transparent. Rain, snow, and ice are largely irrelevant to sub-GHz signals, but they attenuate high-frequency transmissions significantly. The V-band (60 GHz) is so aggressively absorbed by oxygen molecules that its useful range is measured in mere meters.

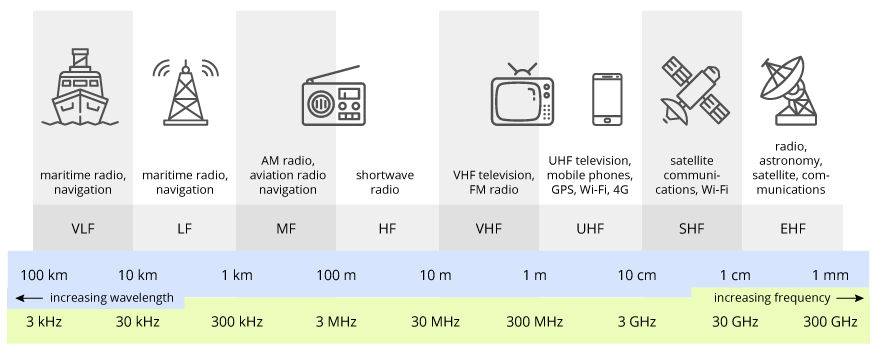

- Shannon’s Law (The Speed Limit): Every wireless system obeys the Shannon-Hartley theorem, which defines the maximum rate data can be transmitted without error. Capacity scales with two variables: Bandwidth (the width of the lane) and Signal-to-Noise Ratio (the loudness of the shout).

- At low frequencies, spectrum is fragmented into narrow lanes (1-10 MHz). Great for low-rate messaging, voice, and control signals, useless for modern gigabit broadband.

- At high frequencies, the lanes widen into massive highways (100-500 MHz blocks). This is essential for moving high-volume data like video, sensor fusion, or compute offload.

- The trade: You can use those wide high-frequency lanes if you can maintain the SNR ratio against the penalties of path loss and weather (and interference). Capacity rises with bandwidth, but so do the demands on link budget and coordination.

The Unequal Map

These physical laws do not distribute strategic value democratically. Some frequencies are naturally suited to long-range broadcast but carry very little data. Others can carry the entire Library of Congress in a second but can’t penetrate a pane of glass.

But in the middle, a few bands hit the “Goldilocks” zone: just enough range to cover a city, just enough penetration to enter a building, and just enough bandwidth to deliver broadband speeds. These are the lanes everyone wants — carriers, defense, aviation, satellite, cloud infrastructure — and they are already quite crowded.

This is the structural root of the crisis: the supply of spectrum is fixed, finite, and non-renewable, but the systems trying to consume it are multiplying. Unlike oil or lithium, we cannot dig for more airwaves. We have to make do with what we have.

You can see this tension most viscerally from roughly 600 MHz to 40 GHz, the zone where the modern American economy, military, and scientific enterprise all operate. What follows is a walk through this neighborhood — the most contested invisible real estate on Earth.

The Spectrum Walk: A Tour of the Contested Atmosphere

The operating envelope for modern civilization spans roughly 600 MHz to 90 GHz. Within this range lies every system that carries the weight of modern American life: the carrier networks, the missile defense shields, the GPS constellation, and the satellite downlinks. Each band serves a distinct function, dictated by the physics we just discussed.

But as you move up the dial, you will find that the strategic pressure is not distributed evenly. Some frequencies are “beachfront property” facing massive overcrowding; others are “high-altitude deserts” that remain technically hostile and sparsely populated. What follows is a tactical tour of the neighborhoods where the American economy, military, and scientific infrastructure actually live.

The Pressure Gradient

Survey this invisible terrain and the strategic bottleneck becomes obvious. The low-band foundation is saturated and cannot scale. The high-band frontier, while vast and powerful, is leashed by the laws of physics. That leaves the mid-band as the only viable maneuver space: the sole zone where range, penetration, and capacity converge, and where global hardware ecosystems already exist at scale.

This is why friction is concentrating in the mid-band – it’s why every new system wants to go. The fights keep happening in this narrow slice of spectrum because, quite simply, there is nowhere else to go.

We have clearly exhausted the capacity of our current regulatory framework to manage this density. We are well past diagnosing whether our current regulatory architecture can manage these conflicts gracefully. C-band-gate and a dozen other fiascos have answered that question.

Scarcity does not have to result in unproductive paralysis. The reason these physical constraints keep turning into national crises isn’t because we run out of spectrum; it’s because we lack the machinery to allocate it efficiently. We are trying to adjudicate high-speed, automated conflicts using a regulatory flowchart drawn up before the invention of the transistor. To understand why the system keeps crashing, we have to look at the architecture itself.

Section 002

A System Built for a World That No Longer Exists

If the physical laws of spectrum are consistent and knowable, the way we Americans govern it is anything but. Our electromagnetic architecture is a patchwork built for an era when radios were narrowband, satellites were a figment of our imagination, and federal agencies could be assigned clean, non-overlapping bands without conflict. That world is long gone.

The Original Sin

The United States pioneered spectrum management with the Radio Act of 1912 and solidified the current structure with the Communications Act of 1934. That legislation created what we might call the original sin of American spectrum policy: bifurcation.

The system split in two:

- THE FCC governs commercial, state, and local users. It is an independent agency, accountable to Congress. If you are Verizon, a local police department, or a guy trying to fly a drone in your backyard, you answer to the FCC.

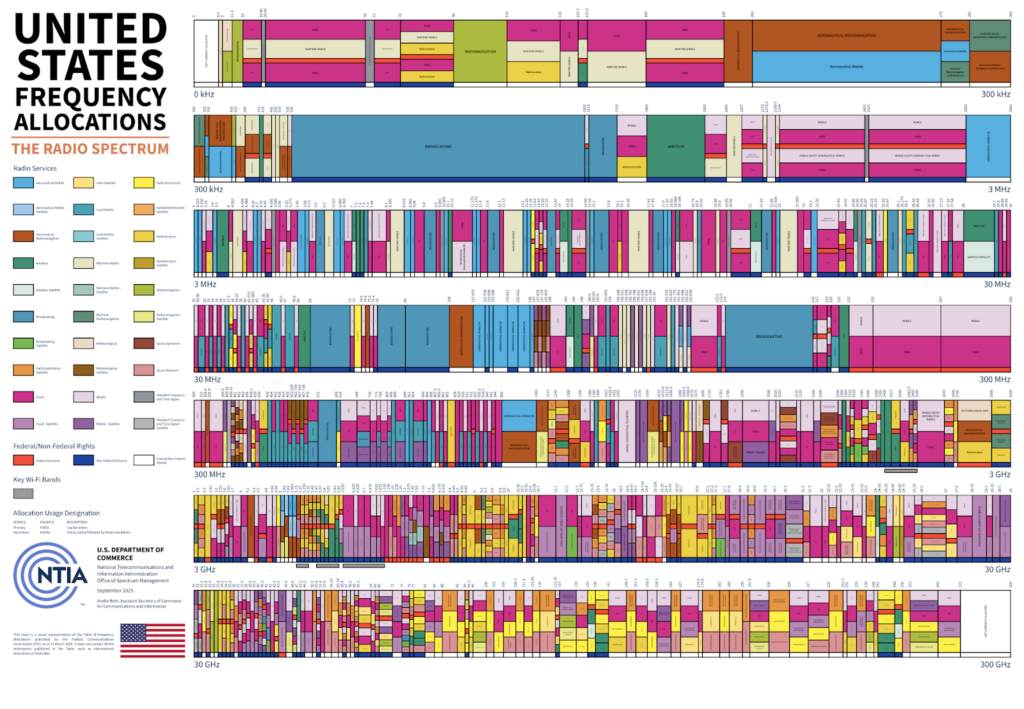

- THE NTIA manages federal users. It reports to the Executive Branch and manages the federal spectrum: DoD radars, FAA safety systems, NASA links, NOAA weather sensors, IC assets, etc.

Bifurcation was tolerable when spectrum uses were sparse and separable. Today, however, the most strategically important bands (~1–8 GHz) are shared space. Commercial 5G sits next to military radar; aviation safety systems operate adjacent to Wi-Fi; satellite downlinks border weather surveillance. The clean lines of 1934 have become a jurisdictional mess.

The Fog of Spectrum

The NTIA oversees federal users through the Interdepartment Radio Advisory Committee, a body originally convened in 1922. Nineteen federal agencies sit at the table. Many of their systems were designed in different eras, for different missions, under different risk tolerances. Progress moves at the pace of the most conservative participant.

The FCC, for its part, is structurally oriented around auctions, licensing, and consumer markets. Its mandate focuses on commercial utility, competition, and economic efficiency. It does not treat spectrum as a national strategic resource; it treats it as a regulated market.

And crucially: there is no single map.

The NTIA and FCC maintain separate, non-interoperable databases. NTIA’s systems track frequency assignments, not real-time use. The FCC’s Universal Licensing System handles commercial rights, but not federal users. Neither system provides live occupancy data, so no one knows who is transmitting where, or when. This makes it nearly impossible to challenge incumbents who claim their band is fully used, because you can’t prove otherwise!

Until recently, there wasn’t even a requirement for FCC and NTIA leadership to meet regularly. Two agencies jointly responsible for the nation’s most contested strategic resource, operating in parallel silos, coordinating by accident.

When a modern system spans both worlds – and increasingly, they all do – there is no coherent adjudicator. Agencies model interference with different assumptions, different equipment profiles, and different risk tolerances. They often work from receiver performance standards written decades ago, because updating them requires coordination across bodies that share no chain of command.

Almost every high‑profile U.S. spectrum “interference” fight of the last decade has turned out to be less a story about rogue transmitters and more a story about fragile receivers. We built critical systems assuming their RF neighborhoods would stay quiet forever, then balked when someone proposed using the adjacent band for high‑power, high‑density services. Technically, the conflicts are usually solvable with better filters, smarter band plans, and some guard bands; politically, they get stuck on a harder question: who pays to modernize the old equipment so the new services can exist?

Three tools of the trade

When two parties want the same spectrum, there are three ways to resolve the conflict: clear out the incumbent, share the space, or fix the radios.

Clearing: The “Pay-to-Move” Model

The traditional approach is to pay federal agencies to vacate a band and move elsewhere, using auction proceeds to cover the bill. Congress created the Spectrum Relocation Fund in 2004 to pay federal agencies to move. It has funded $1.5B in relocations, most notably clearing 1710–1755 MHz for AWS-1 auctions. But the process is glacial: years of cost estimates, OMB negotiations, and congressional notifications.

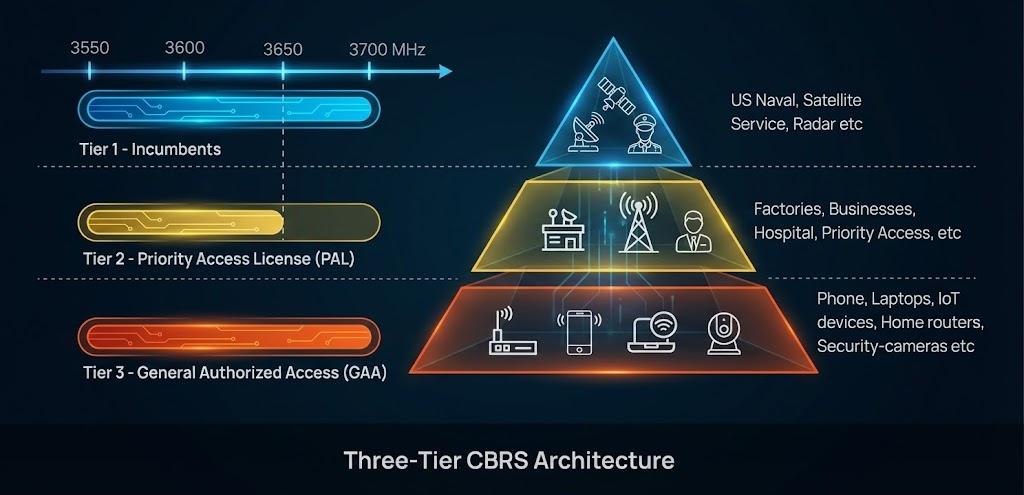

Sharing: The Time-Share Model

Instead of permanent eviction, we can use software to coordinate access in real time. Systems now exist that allow commercial users to “borrow” military spectrum when it isn’t being used, powering down automatically when an incumbent needs the lane. While technically proven, this approach is often blocked by security concerns; agencies fear that revealing when they are transmitting reveals too much about how they operate.

CBRS (Citizens Broadband Radio Service) is the most sophisticated sharing regime the U.S. has ever deployed. The 3.5 GHz band is split into three tiers: incumbents (Navy radar) get priority, PAL licensees pay for protection, and GAA users get leftovers managed by a Spectrum Access System (SAS) that coordinates in real time. SAS knows where Navy radar is operating and powers down commercial users automatically. Crucially, this model works, with 150 MHz of previously locked federal spectrum now in commercial circulation.

Mitigation: The “Better Gear” Model

Often, interference isn’t caused by a “noisy” transmitter, but by a “deaf” receiver that can’t filter out background noise. The engineering solution is to upgrade legacy equipment with modern filters so adjacent bands can coexist. The political reality, however, is gridlock: incumbents invariably refuse to pay for upgrades, effectively killing new networks to protect obsolete hardware.

The Incentive Structure

Charlie Munger liked to say: show me the incentive, and I’ll show you the outcome.

The outcome of America’s bifurcated spectrum system is that the U.S. military, the largest owner of federal spectrum, occupies ~60% of the prime mid-band. Not because the Pentagon is malicious, but because the system gives federal incumbents every reason to hoard and no mechanism to force efficiency. Spectrum held is spectrum defended. Spectrum released is spectrum lost forever.

The commercial side isn’t blameless either. Carriers want exclusive licenses. They’ll pay billions for the certainty of interference-free operation. Sharing arrangements introduce complexity, and complexity introduces risk. Everyone wants a fence around their frequencies.

The result is a system optimized for incumbent protection rather than national capability. Bands sit underutilized because proving underutilization requires data that nobody collects, and diligence that nobody can conduct. Reallocation takes decades because coordination requires consensus across bodies designed never to reach it. And when conflicts erupt, they typically get resolved through political brinksmanship rather than technical adjudication.

The inefficiency of federal spectrum management is the natural consequence of institutional inertia. The U.S. proposed its first spectrum auction in 1959 but, crippled by bureaucratic resistance, delayed it until 1994 – even as the concept became a global revenue model that earned its American designers a Nobel prize.

The pattern continues today: Despite U.S. carriers achieving a 42× improvement in spectral efficiency on the slice of frequencies they do use, the paralysis over new mid-band spectrum means consumers face the very real prospect of slowdowns and degradations within two years.

Things got so contentious that Congress actually allowed the FCC’s auction authority to lapse in March 2023. For the first time in 30 years, the U.S. lost the legal ability to auction its own airwaves. While the authority has since been restored in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, for nearly two years America unilaterally disarmed itself in the global race for connectivity—all because the system had ground itself into paralysis.

Section 003

The Spectrum Island

While we in America have been fighting our intramural airwave turf wars, the rest of the world has moved on.

Global technology standards follow the widest path, and manufacturing chases volume. If most of the world uses the same frequencies for 5G, that’s where device manufacturers will focus their engineering effort, where equipment gets optimized, and where costs will come down.

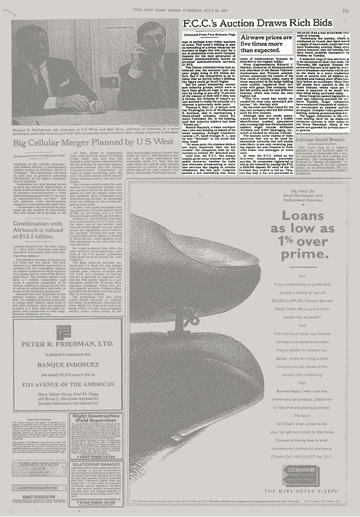

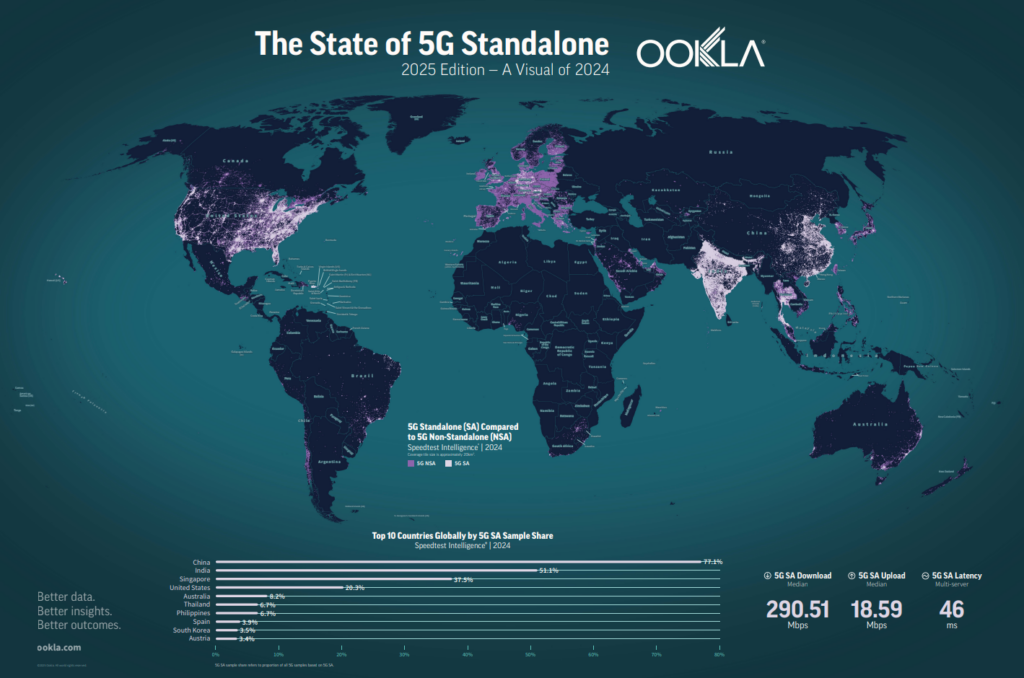

In the late 2010s, the world made its choice. Europe allocated 3.4–3.8 GHz for 5G. The UK, France, Germany, and the Netherlands all standardized on this same “n78” band. South Korea deployed on 3.4–3.7 GHz, and Japan opened the 3.6–4.1 GHz range. China allocated 3.3–3.6 GHz and then, in June 2023, aggressively moved to identify the entire 6 GHz band (6425–7125 MHz) for licensed mobile use—the first country in the world to do so.

The result?

Nearly 50 countries have now standardized on band n78 (3.3–3.8 GHz). Today, 2,343 different 5G device models support this specific band, making it the most supported 5G frequency on Earth.

Close, but no cigar.

Though the global ecosystem organized itself around a single standard, the U.S. missed the party. We auctioned 3.7–3.98 GHz (C-band), a range that sits adjacent to the global standard but misses the critical “Lower 3 GHz” overlap. That 3.1–3.45 GHz slice—the heart of the global roaming band—remains locked down by the Pentagon. This means the very frequencies the world chose for 5G are the frequencies America uses for missile defense radar.

Beijing noticed, and seized the opportunity. China has allocated ~70% more licensed mid-band spectrum for 5G than the United States.

By 2027, the U.S. is projected to face a spectrum deficit of 400 MHz; by 2032, that gap could balloon to 1,400 MHz.

As America adjudicates its myriad internal disputes, China is working the refs – lobbying the ITU (International Telecommunication Union) to standardize the global stack on the bands it already uses. This strategy finds ready allies, as China exports its spectrum architecture to the Global South, to Africa, to Southeast Asia: places building their networks on Huawei gear, with Chinese financing.

If China, Europe, the rest of Asia, and the rest of the world all use the Lower 3 GHz band for 5G, and the United States bans it because of legacy military radars, there is only one way to describe the outcome: the U.S. will find itself on Spectrum Island.

And this is not a hypothetical. At the 2023 World Radiocommunication Conference – the key global forum for setting spectrum standards – America’s failure to develop a unified national position was described as a “low point for U.S. influence,” where “America was excluded from key negotiations due to not having developed clear positions.”

If you’re on Spectrum Island, the world does not want your technology. Global manufacturers like Ericsson, Nokia, and Samsung prioritize building chips and radios for the “Global/Chinese” bands because that’s where the volume is. The U.S. will be forced to buy bespoke, expensive equipment tuned to our unique, fragmented frequencies. This increases costs for companies, which get passed on to consumers. This will slow adoption, make our infrastructure less capable, and create the conditions for Huawei and ZTE to dominate the global market by offering cheaper, harmonized networking equipment that the U.S. cannot match.

In short: if the world runs on Chinese frequencies, the world will run on Chinese gear.

Section 004

Why Deep Tech Needs Airwaves

We tend to think of 5G in terms of consumer convenience – faster downloads, better streaming, improved video calls. (Ryan wrote an entire primer on this a half-decade ago.) And so the spectrum crisis is usually framed as a consumer inconvenience: slow downloads at the airport or dropped calls in a stadium.

This is a smokescreen. The real casualty of our airwave paralysis is our physical capacity to build the future.

The U.S. doesn’t have enough mid-band spectrum. This means we don’t have enough spectrum to build the factories of the future. China, by contrast, has allocated the 3, 4, and 6 GHz bands in contiguous blocks, specifically designed to run the factories of the 21st century.

Simply look at how, where, and whether industrial and national security users get what they need. These sectors impose requirements that consumer networks cannot meet. Consider the modern ‘lights-out’ factory: an autonomous assembly line is a choreography of risk, where hundreds of mobile robots might move simultaneously. AGVs shuttle parts between stations, robotic arms swing thousand-pound chassis, and vision systems tracking micron-scale tolerances.

These systems need to communicate with absolute precision. Each packet must arrive on time, all the time. The industry standard for mission-critical industrial automation is “five nines” reliability (99.999%), which translates to just over five minutes of downtime per year.

WiFi cannot deliver this. The protocol is an unlicensed free-for-all where your multi-$M welding bot competes with the breakroom microwave or a passing Bluetooth headset. WiFi has latency spikes, jitter, and no quality-of-service guarantees. If a packet drops and a robotic arm hesitates for 10 ms mid-swing, you could destroy a $50,000 fixture — or worse, put a worker in harm’s way.

Industrial 5G solves this. By using licensed, dedicated spectrum, private 5G networks can deliver <1ms latency, deterministic timing, and five-nines reliability. But…to state the obvious, this technology only works if the spectrum to enable it exists. If the frequencies are fragmented, hoarded by legacy radar, or trapped in regulatory limbo, the factory just won’t get built – or it will require expensive, sub-optimal workarounds.

The same logic applies across many sectors where Per Aspera‘s readers operate: BVLOS drones, edge AI deployments, precision agriculture, and more.

What Could Go Right? Look to 4G LTE

In the late 2000s, the U.S. made an prescient bet that defined the digital economy. The FCC cleared and auctioned the 700 MHz band — prime “beachfront” spectrum freed up by the transition to digital TV. American carriers deployed early, and they deployed fast. By 2012, the United States accounted for 60% of the world’s LTE subscribers.

This head start is why the “App Economy” speaks English. Uber, Instagram, DoorDash, mobile streaming, the entire smartphone software ecosystem — all of it was built on the foundation of American 4G leadership. The result was an economic engine that contributed nearly $700 billion annually to U.S. GDP by the end of the decade, generating trillions in downstream value.

If 4G was a consumer revolution, 5G and 6G are industrial revolutions. The killer apps of the 4G era (social media, ridehailing, video) connected people to services. Today and tomorrow’s networks will connect machines to machines: autonomous logistics, industrial automation, “lights-out” manufacturing, and real-time AI inference at the tactical edge.

This brings us back to the map.

If we lead the allocation of 3–7 GHz spectrum, the companies and capabilities will get built here: American factories become the most automated in the world, American logistics networks the most efficient, American farms the most productive. We will finally have the digital substrate required to reindustrialize.

But if we let spectrum policy drift while fighting intramural turf wars, those capabilities will be built in Shenzhen, Seoul, and Munich. We will consign ourselves to sitting out the next industrial revolution simply because we couldn’t get our agencies to agree on a map.

Section 005

Golden Dome Is the Perfect Case Study

The entire argument over America’s spectrum future collapses onto a single, critical piece of real estate: the Lower 3 GHz band (3.1–3.45 GHz).

The band is currently occupied by the Department of War, which relies on it for the active, operational backbone of America’s integrated air and missile defense. Specifically, the band hosts shipborne radars like the AEGIS SPY-1 and its successor, the SPY-6, as well as Airborne Warning and Control Systems (AWACS). This is why the Pentagon will not readily cede the airwaves: the 3 GHz band maintains the surveillance envelope protecting the homeland and forward-deployed fleets.

The urgency has only increased with the “Golden Dome” initiative, a directive to build a next-generation, multi-layered missile defense shield. The plan explicitly relies on the existing 3 GHz radar infrastructure as its foundation.

This reality has created a paralysis in Washington, framed as a zero-sum choice:

- The Pentagon’s Case: “Reallocating this band puts the homeland at risk. We cannot move these radars without billions of dollars we don’t have and decades of time we can’t afford.”

- The Commercial Case: “Hoarding this band suffocates the digital economy. It cedes the future of 5G and Embodied AI to competitors who aren’t afraid to clear the airwaves.”

Both sides are right. And both sides are missing the point, as this “choice” is really a false dichotomy.

This is not an either/or situation. We need both military and commercial users on the same midband spectrum because they ultimately need the same thing. The DoW’s own strategy – JADC2 (Joint All-Domain Command and Control) — requires massive bandwidth at the tactical edge to connect sensors and shooters. It relies on the scale and innovation of commercial 5G.

If the U.S. remains a Spectrum Island, the Pentagon isolates itself from the global technology curve. While allied and competitor nations build dual-use AI and autonomous systems on standardized 3 GHz bands, the U.S. military will be forced to order expensive, custom-built hardware for a unique frequency ecosystem nobody else uses.

The core of the problem, and its solution, lies in the hardware itself.

The Radar Problem

The AN/SPY-1 radar, currently mounted on most AEGIS cruisers, is a marvel of Cold War engineering – but it is a spectral dinosaur. As a Passive Electronically Scanned Array (PESA), it uses a massive central transmitter to blast huge amounts of energy into the S-band. It is a “noisy neighbor,” spilling significant RF energy outside its assigned lane. This makes it difficult for commercial 5G to operate next door without getting fried or disrupted by RF interference.

Enter the AN/SPY-6, a modern, new radar currently deploying on Flight III Arleigh Burke destroyers. An Active Electronically Scanned Arrays (AESA), it is digital, precise, software-defined, and more resistant to jamming. Unlike its analog predecessor, it forms tight, “pencil-thin” beams that stay strictly within their lanes, allowing commercial networks to operate in adjacent bands without interference.

The solution is modernization, not eviction. By upgrading the fleet to SPY-6 and similar modern radars, we achieve a double victory: the Navy gets a sensor that is 30× more sensitive than the legacy system, and the economy gets the spectrum it needs to compete with China.

The obstacle is the capital cost of a refit. Upgrading a ship is expensive, and may take it out of service for months or years. But this is a solvable problem if we change how we view the asset.

Section 006

The Solution: A “Grand Bargain” for Modernization

Our spectrum “shortage” is really an efficiency problem, caused by government users squatting on valuable real estate because they have no incentive to move. This calls for nothing less than a Grand Bargain for spectrum modernization. Here’s how it should work.

001 // Clean up our house. We cannot negotiate with the world if we cannot manage our own government. The contentious NTIA-FCC relationship does us no favors. We need to streamline and link the databases to create a “single pane of glass” view of who is using what frequency and when. We must standardize interference analysis so that the FAA and FCC aren’t using different math to calculate safety risks, preventing new fiascos before they start.

002 // Supercharge the SRF. The Commercial Spectrum Enhancement Act of 2004 established the Spectrum Relocation Fund (SRF), a brilliant mechanism that allows auction revenues to pay for federal clearing/relocation costs. We should make this an order of magnitude larger. And let’s start by auctioning the Lower 3 GHz band to commercial users, a transaction that would likely fetch in excess of $50B. We can use this revenue explicitly to pay for radar upgrades, new ship builds, and fleet modernization. This is a win-win: better 5G for the economy, better radars for the Golden Dome. The Pentagon must stop viewing spectrum reallocation as a measure to be avoided at all costs, and start viewing it as a source of capital.

003 // Incentivize the Squatters. Right now, agencies see spectrum as a free good. To fix this, we need to change the accounting. Agencies should not just be reimbursed for moving costs; they should be allowed to keep a significant percentage of auction proceeds for discretionary modernization (a concept central to the proposed Spectrum Pipeline Act). Give the Navy a bounty for efficiency. Make spectrum release the most profitable line item in their budget.

004 // Get off the damn island. We need to harmonize with the rest of the world and get off of Spectrum Island. This means aligning U.S. allocations with the 30+ nations already using the Lower 3 GHz for 5G, including key allies like the U.K., Japan, and South Korea. By harmonizing our spectrum, we influence global standards and build a trusted supply chain that does not rely on Chinese-subsidized hardware. We stop building boutique radios for a market of one.

005 // Build a programmable spectrum layer. Not every conflict needs a permanent winner. In many times and places, two systems simply do not need the same band at the same time. The Navy needs the Lower 3 GHz band off the coast of San Diego; they do not need it in downtown Chicago. Instead of crude “Static Sharing” (permanent exclusion zones that leave spectrum dark 99% of the time), we need Dynamic Spectrum Sharing (DSS). We should stand up and scale a national, software-defined coordination layer that can time-slice and geofence access. When a radar is active in a given sector, commercial systems back off. When it is silent, commercial systems light up at full power.

Wrap

The United States spent the last century building a theory of material power: steel, oil, and atoms. We have developed theories for semiconductors, for energy, and for critical minerals. We even have a theory of soft power. But we have yet to build a theory of invisible power: a theory of spectrum.

We treat airwaves as a regulatory nuisance to be managed, or a commodity to be traded, rather than a strategic asset to be mobilized. We ask two agencies to fracture the map into bureaucratic silos, and hope for the best. We auction bands to the highest bidder and assume the invisible hand will sort it out.

This works until it doesn’t — until the airlines are writing panicked letters to the White House, until the auction authority lapses, and until our allies build interoperable systems and we cannot join. The result is a nation that invents the future but cannot deploy it.

A theory of spectrum would start from a different premise: that the electromagnetic environment is a theater of competition as real as the Pacific or the Arctic, and that the nation that masters it will shape the century. The nation that ignores it will be shaped by it.

So, we must resolve to answer a simple question:

Do we govern the airwaves, or do they govern us?