The United States is spending tens of billions to acquire the very same critical minerals that we throw away every day.

Last week, the White House announced Project Vault: a stockpiling initiative that puts up $10B in EXIM financing plus $2B in private capital to stockpile dozens of critical minerals as a hedge against Chinese supply disruption. For its part, the DOE is earmarking nearly $1B for projects across the critical minerals value chain, including some focused on “unconventional sources” such as waste streams and recycling.

This is the most aggressive domestic critical mineral push in recent memory. It’s overdue, and it’s a big step in the right direction. We’re very glad it exists. Still, we can’t help but wonder if we as a nation are overlooking a potent lever from the unlikeliest of places: our trash cans.

Across announcements and strategic plans that have been released in recent weeks and months, recycling remains a small, scattered line item, especially when sized up against the scale and spend of the stockpiling program.

So, today’s question: Why is recycling a rounding error in our strategy to break the critical mineral chokehold?

The Case For Recycling

Even though it’s the shortest month of the year, this February alone, American consumers and companies will dump on the order of half a million tons of dead electronics. Today, the very day you are reading this, we (Americans) will dispose of something like 416,000 phones, 142,000 computers, and tens of thousands of cars — most of them headed to landfills, shredders, or low-road export channels.

Now, we’re not deploying shock-and-awe-via-statistics to tut-tut our fellow Americans or deliver an eco-sermon. We like polar bears and “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” posters just as much as the next guy, but this essay isn’t about virtue. It’s about leverage – straight from the School of Realpolitik.

You see, much of the e-waste being put to digital pasture is laden with neodymium, dysprosium, and cobalt – already mined, already refined, already in the very alloys our government, defense industrial base, and other critical industries are all so desperate to secure.

Conservatively, a third of U.S. e-waste still ends up landfilled or burned, and somewhere between a tenth and two-fifths of ‘recycled’ devices quietly leave the country. All told, today recovered REEs from end‑of‑life products make up just ~1% of annual U.S. demand.

We are spending tens of billions to dig more rock and build bigger vaults, and an order less to advance recycling. Reducing our overseas dependence has no silver bullet. Mines, refineries, science, finance, and alliances all must play their part. But recycling, in our estimation, deserves to be more than a footnote. Below, we offer our eight reasons why.

1. The single-use problem

You know what they say: One Man’s Trash Is Another Man’s Concentrated Feedstock. E-waste provides a valuable stream of copper, gold, and rare earth magnets.

To give an example: A neodymium magnet from a hard drive is ~30% rare earth by weight. Typical ore runs below 2%. That’s a 15x enrichment factor before you touch a chemical.

From first principles, this seems strategically backwards, right? We import high‑value materials embedded in finished goods, then export or bury them at end‑of‑life.

2. Decoupling from refining chokepoints

Most cocktail party chatter on the matter (unclear if this has ever actually happened) conflates mining and refining, but as you, dear reader, likely already know, our chokepoint is midstream processing.

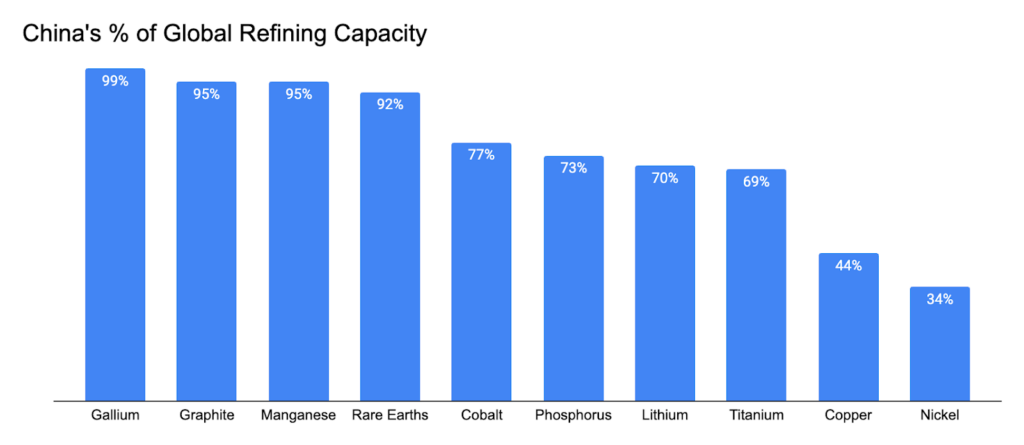

- China now controls roughly two‑thirds of global rare earth mining — a big number, but still technically manageable with allies in Australia, Canada, and Brazil.

- By contrast, it dominates the midstream, with upward of 90% of global rare earth refining and magnet production.

From time to time, we see the armchair finance or tech pundits on X comment that rare earth refining seems like a “very solvable problem.” And it is! You “just” need the chemical engineers, the permits, the hydrochloric acid supply chains, and some time to spare. We had this processing capacity and chemical tribal knowledge but systematically offshored it in the ‘90s and 2000s. Getting back into full swing will take time, some real political battles, and likely a willingness to pay a premium for cleaner processing techniques, because large-scale rare earth solvent extraction is one of the dirtiest, most chemically complex industrial operations we know how to run.

Good news. Not only does recycling allow you to avoid some of the aforementioned ugliness, it also changes where and how you can re-enter the value chain. A magnet harvested from a hard drive or a motor is already a finished alloy (not a mixed rare ore or crude oxide). If we’re able to salvage more from recycled magnets, motors, and battery materials, we can re-enter the value chain after the most chemically complex, highly pollutive, and most China-dominated step (e.g., large-scale solvent extraction and oxide separation), which is conveniently also the point where domestic manufacturing capacity is strongest.

3. Independence for heavy REEs

Light rare earths (La-Nd) can be mined at Mountain Pass in California, or at prospects in Allied jurisdictions like Canada, Australia, and Greenland. Heavy REEs are more geographically constrained, as they largely originate from ionic clay deposits in southern China and Myanmar.

But! Good news again. We’ve been importing heavy REEs for decades in our finished products – and they can be found in great quantities across spent hard drives, MRI machines, EV motors, and wind turbines. Dysprosium and terbium, two of the heavy REEs that folks talk about most at the fictional cocktail parties, allow permanent magnets to function at high temperatures in jet engines, missile guidance, and submarine drive motors.

For our defense industrial base, beyond the stockpiles we’re building now, it would seem that the domestic e-waste stream is one of the only scalable sources of defense-critical heavy REEs that doesn’t route through Beijing.

4. Resilient unit economics

Rare earth markets are notorious for boom-bust cycles, often dictated by Chinese dumping ‘export policy’ rather than market fundamentals. A brief history, courtesy of Per Aspera #012:

“From the 1960s through the ‘80s, California’s Mountain Pass mine pumped out 70% of the world’s light rare-earth oxides: the neodymium, samarium, and europium that lit up color TVs and guided Cold-War weapons. America sold oxides much the way Saudi Arabia sold oil.

Then, two curves crossed in the early ‘90s. Stricter U.S. environmental rules and rising labor costs coincided with China declaring REEs a “strategic resource.” The ascendant industrial power aimed not to compete, but conquer. State miners operated with zero-return requirements while enjoying 13% VAT export rebates. In the late ‘90s, Chinese state-backed firms acquired GM’s Magnequench, redomiciling America’s premier magnet technology to Tianjin.

Meanwhile, Mountain Pass bled cash, suffered spills, and shuttered in 2002. A $1.7B private equity reboot began in 2008, just in time for Beijing’s next move: restrict exports in 2010, spike NdPr oxide to $340/kg the next year, coax fresh Western investment, then crash the price back to $60 by 2012–13. Mountain Pass’s operators filed for bankruptcy in 2015.

Two years later, MP Materials acquired the site and resumed operations in 2018. It kept shipping concentrate to China for processing until this year, when it cut exports and the Pentagon stepped in with a 15% equity stake and a $110/kg floor contract. MP’s Fort Worth, TX magnet plant came online this year, with nameplate capacity targeting 10,000 t/yr by 2028.

The story of Mountain Pass is one of both A) strategic amnesia, and B) strategic reawakening, as Washington rouses itself from a protracted industrial sleepwalk.”

With this brief history lesson in tow, we now return to the main topic at hand. Compared to mining and refining, recycling starts from a different physics and cost equation:

- 30% concentration feedstock instead of sub-2% ore = fewer chemical steps, less water, less energy, less waste.

- Academic and industry studies of magnet‑to‑magnet recycling indicate potential production cost reductions on the order of 30–50% versus virgin material routes, due to higher feedstock concentration and fewer steps.

- High-fixed cost greenfield mines are more vulnerable to market cycles (and Chinese price manipulation).

- Recyclers could have lower breakevens and a higher inherent margin cushion, making them harder to kill.

5. Speed to Market

Time is not on our side.

It takes an American operator roughly 7 to 10 years just to permit a new project. A 2024 S&P Global report found that the U.S. has the second longest lead times in the world for developing a new mine, with an average discovery-to-production timeline of ~29 years. Even under an optimistic reform scenario, which seems likely, new mines still won’t be able to solve short‑to‑medium‑term deficits.

A recycling facility can be sited, permitted, and online in a few years (typically 1–3, almost always under 5). Cyclic Materials, for example, recently announced an $82M rare earth recycling plant in McBee, SC, which is scheduled to come online before any new domestic mine breaks ground. Other state permitting examples show multi-year but much shorter timelines: on the order of 1-5 years for stationary recycling installations, with some classes capped at two-year siting windows.

If the U.S. needs incremental supply in this decade, recycling is a fast, meaningful lever to bring it online on the same time horizon that a strategic stockpile could theoretically be drawn down.

6. Adding Geographic Armor

Mountain Pass sits in the Mojave Desert, connected by a single rail corridor through empty terrain. New remote mines require enormous infrastructure investment — rail, roads, water — just to move material from pit to plant to port.

Today, this journey looks something like: remote pit → rail → port → foreign refinery → back again. And, even as we wean ourselves off the last two steps, we will still need to push critical materials through a narrow path susceptible to sabotage and security risks.

Americans are nothing if not materialistic, which means we generate a lot of waste. And we are mostly an urbanized society, which means most e-waste is generated near where the manufacturing happens: in cities, within industrial belts, and near logistical hubs. A distributed network of regional recovery facilities presents a smaller, more redundant attack surface than a handful of mines and long, exposed supply lines. The just-in-time trash model is inherently harder to coerce or cut.

7. Elasticity Under Stress

Mines are wedded at the hip to the geology they sit on, with the ore body determining the output mix for decades. If wartime demand swings to a different set of elements, a mine cannot pivot as nimbly. Recycling plants, by contrast, can shift the composition of their feedstock within a broad envelope. They can shift from lithium-ion batteries to NdFeB magnets to nickel-metal hydride cells depending on immediate demand. This “recover what is needed now” capability is exactly what you want if you’re planning for shocks rather than smooth curves.

8. Circular Sovereignty

Project Vault’s loan authorization and private plus-ups aim to build a critical minerals reserve modeled loosely on the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, which can provide producers with a buffer when markets seize up. But stockpiling is – by definition – a finite, defensive measure. If a blockade or export ban lasts long enough, and the domestic capacity to refill it is not there, you’ll eventually run it down. Recycling, on the other hand, is inherently renewing. Every ton of Nd, Co, or Dy recovered and recirculated is a ton that no longer depends on there-and-back logistics loops and foreign processing. And over time, that raises the effective mineral density of the U.S. economy.

It’s Time to Mine (And Close the Loop)

Mines, alliances, science, and stockpiling will all play an important role in this push. But $12B for storage and loose change for recovery sets us up for a stockpile with no replenishment plan.

Fortunately, private capital is starting to mobilize, from Redwood’s battery campuses to Cyclic’s new REE facility in South Carolina. And the DOE is lining up nearly $1B across the critical minerals value chain, with roughly half aimed at battery materials processing and recycling, another quarter for byproduct recovery, and a final tranche for REE recovery from waste streams.

On nearly every dimension that matters for near-term supply – capital intensity, time to first output, emissions footprint, and foreign dependency – recycling handily outperforms. If the goal is incremental domestic supply in the 2020s, recycling is the highest-leverage tool at our disposal – because it’s the only one that can turn already-here, already-refined, already-in-country material into feedstock on a product cycle, rather than a decadal permitting timeline.