Introduction

Foreword

On a humid summer evening in 1947, a seven‑year‑old boy from the Bronx lay under the Hayden Planetarium’s dome, watching a universe unfurl above him. Stars and planets wheeled in slow procession, painting a cosmos far more vast than anything he’d known. At that moment, he understood: If we could imagine beyond our supposed boundaries, we could travel beyond them too.

That boy was me.

I had glimpsed infinity and thought: we could go there. And I resolved to spend my life chasing this promise. I would grow up to study engineering in college. I joined TRW, where I built space systems that could intercept Soviet ballistic missiles during the Cold War. The work was hard. We were locked in fierce technological competition with formidable Soviet scientists. But we were driven by conviction that American ingenuity could outfox any adversary.

When I became NASA administrator in 1992, the Cold War was ending and budgets were shrinking. I faced a new challenge: do much more with much less. I made faster, better, cheaper the agency mantra, relentlessly pressing my teams, primes, and suppliers. And despite the constraints, or perhaps because of them, we did great things. We repaired Hubble, assembled the ISS, and reached farther into the universe than ever before. Hell, we even learned how to live and work off of planet Earth!

I was NASA’s longest serving boss. After finally hanging up my government cleats in 2001, I would go on to partner with Nobel Laureate Gerald Edelman to emulate neural function in rudimentary robots — essentially, an early attempt at building brain-based computing devices.

We were chasing what I still believe to be the ultimate frontier: human cognition itself.

But today, I write with profound alarm. I worry that we are surrendering the very cognitive capacities that let us dream of the stars and build machines to reach them. The digital barbarians are at the gates, and we’re the welcoming committee.

Section 001

The Cognitive Debt Crisis

We face an epidemic no one wants to name: a compounding “debt of mind.” Symptoms of this affliction may include offloading deep thought, surrendering to convenience, and dodging every intellectual discomfort.

Like financial debt, it starts small: a quick Google search here, a ChatGPT query there. But compound interest is merciless. Each cognitive shortcut weakens the neural pathways that transform effort into expertise.

👆This is one of many examples that alarm me. Source: FT.

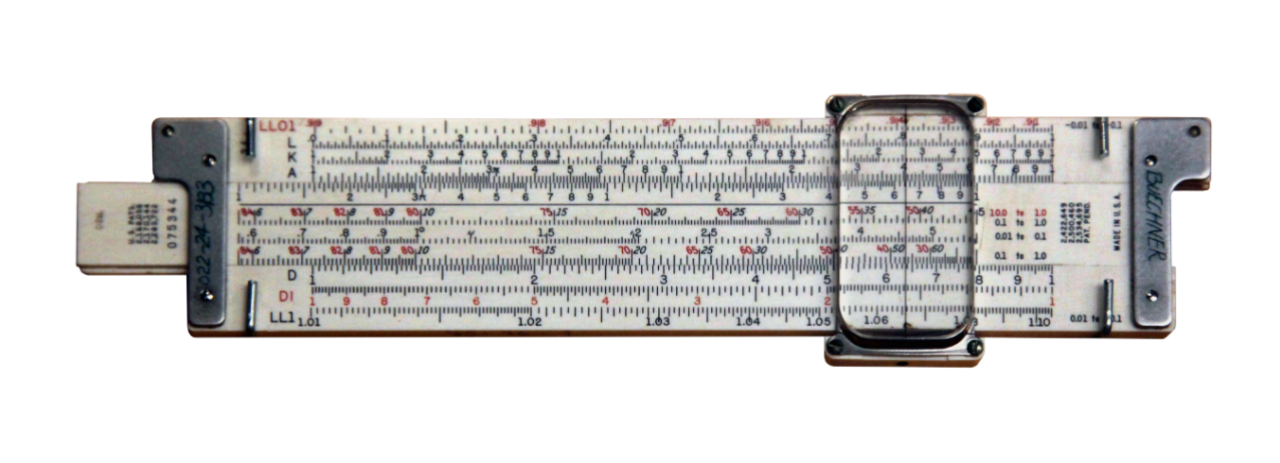

I still remember picking up my first slide rule as a freshman engineer, before calculators were ubiquitous. It seemed magical compared to the log tables and manual calculations I’d had to master. Wielding a humble slide rule, I could tackle complex problems at a speed my analogue predecessors could only dream of.

The humble tool accelerated computation but it did not replace comprehension. To work through a difficult problem, you engaged your brain fully, committing mental cycles from premise to solution. This had costs, measured in tedium and time. But repetition built intuition, and by working a problem deeply from beginning to end, I started being able to make sense of whether a proposed solution made sense or was wildly off.

The same holds for memory. I still retain dozens of phone numbers from decades past: our first family phone from the late 1940s, NASA switchboards from 25 years ago, and colleagues’ direct lines. I can picture their faces and recall their children’s names.

This intuition and recall, I believe, are driven by nurture, not nature. Allow me to explain.

In 1949, when I was nine, psychologist Donald Hebb published a theory that revolutionized neuroscience: neurons that fire together, wire together. Repetition sculpts the brain, carving pathways that transform conscious effort into automatic competence. With successive repetition, you carve deeper neural pathways, developing intuition so fast it feels like instinct.

My father, a biologist, immediately grasped the implications of Hebb’s work and applied it to my upbringing, helping me build my brain through repetition, resistance, and relentless practice. I practiced the clarinet until music flowed without thought, and drilled mathematical theorems until they became reflexive.

People ask me how I still work deals at 85 years old. Simple: I never stopped training.

Today, at 85, I am still designing next-generation space and defense systems that will serve our nation long after my generation is gone. I regularly solve complex problems in my head without digital help, just to keep the blade sharp. I recall faces without checking LinkedIn. To the (occasional) chagrin of my dear wife, I often try my hand at navigating without GPS.

This is the first lesson: the brain is like a muscle. Use it, or lose it. As Hebb taught us, the pathways you exercise become superhighways. When you outsource thinking to a machine, you’re choosing which roads to pave and which to let crumble.

Choose carefully. The infrastructure you build today determines where you can travel tomorrow.

Section 002

The Velocity of Surrender

We have always sought tools to amplify our capabilities. Each generation gets a new cognitive prosthetic: the slide rule, the calculator, the search engine, the generative pretrained transformer.

Who among us hasn’t reached for their phone, laptop, or chatbot of choice when faced with a tricky problem? And why shouldn’t we? We are pragmatists, not monks. The occasional cognitive delegation feels harmless, even sensible – a small withdrawal from the mighty bank of mental effort.

Why is it that this time feels different?

Previous tools automated discrete cognitive functions while requiring human oversight. Calculators compute but you structure the problem. Search engines retrieve but you choose the destination. You still have to formulate questions, interpret results, and generally maintain cognitive control.

But today’s AI is already strong enough to execute entire cognitive loops. ChatGPT can write your whole argument, build your presentation, and generate anticipated objections.

This is the leap from “tool that helps me think” to “tool that thinks for me.”

What if the person becomes a pass-through…a biological wrapper for machine intelligence?

Here’s a thought experiment, taken to the extreme:

A bright college student starts using AI to polish essays. Just a touch-up, he thinks. Works great, so he lets it outline projects. Then complete them. Pretty soon he’s piping everything through his LLM — texts to friends, witty openers for dating apps, and job interview answers that he can effortlessly parrot. He lands a corporate gig. Now he’s copy-pasting ChatGPT outputs all day long, a human middleman between prompt and presentation. Years go by. The cognitive capacity for empathy, argument, improvisation — hell, even for critical thinking itself — have atrophied from disuse. He cannot write an email without AI. Can’t structure an argument. Can’t crack a normal-sounding joke when in the presence of fellow humans. What began as augmentation ends as a self-inflicted lobotomy.

Extreme? Sure. Science fiction? Today, maybe. But if you think this is beyond the pale, you are not paying attention. And that’s what keeps me up at night.

Are we using the tools, or are the tools using us?

When an entire civilization chooses the path of least resistance, simultaneously, and when the exception becomes the rule, who’s using whom? A generation that can’t navigate without phones loses the neural architecture that spatial reasoning builds. A generation that offloads writing, analysis, and creative problem-solving wholesale to the machine risks losing the capacity to develop what makes us human.

“We shape our tools and thereafter they shape us”

Marshall McLuhan saw this coming decades ago.

Look, I am no technophobe. I am not coming from a place of hubristic paternalism (or at least I hope not). This isn’t a case of a Boomer pining for a bygone era, or a slower societal pace. I am aware of history’s cycles of moral panics.

I’ve spent my life building technology. I am utterly fascinated by AI’s possibilities and frequently use it as a thought partner. But what I’m seeing unnerves me.

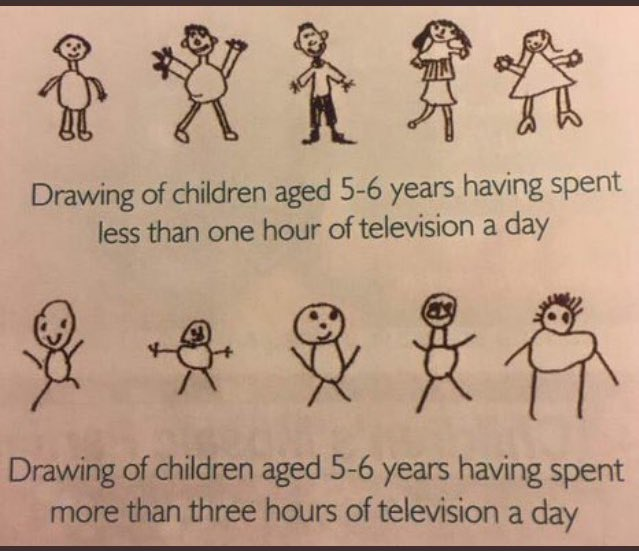

Look at these drawings by five-year-olds: detailed art from low-screentime children, and crude scribbles from heavy viewers.

The visual metaphor seems perfect: excessive screen time stunts cognitive development. Well, it turns out that socioeconomic status, not screen time, predicted the difference. But this picture has made the rounds on social media because we desperately want to believe it. That desperation is the data point.

Because the real evidence is mounting elsewhere, and it’s quite damning:

- Half of American teens spend four or more hours a day on screens (which the CDC correlates with poor sleep, fatigue, depression, and anxiety.)

- The College Board recently shortened SAT reading passages from 750 words to 150, capitulating to our post-literate era and our kids’ atomized attention spans.

- Roughly 40% of high schoolers report having read zero books for pleasure.

- Columbia freshmen arrive at the prestigious university having never completed a single book, while Georgetown students struggle with a 14-line sonnet.

We’re watching the first generation whose brains formed around always-on digital simulation and infinite feeds. We’ve done our kids a disservice by rewiring human cognition for fragments, instant answers, and constant dopamine drips. These minds parse in tweets, think in TikToks, and process reality through algorithmic filters that mediate 20% of our daily lives.

The brain adapts to its diet. Feed it fragments, and sustained thought will starve. Feed it instant answers, the questioning instinct atrophies. Feed it pre-digested opinions, critical thinking withers away.

When cognitive debt compiles and compounds into cultural default, we face a civilizational challenge.

When shortcuts become habits, habits become culture, and culture shapes civilization, where does that leave democracy? Apparently, fewer than 40% of Americans can pass the citizenship test that 90% of immigrants ace. Among Americans under 45, over 80% fail. Many young adults cannot name the three branches of government — the basic architecture of their own democracy.

A republic requires citizens who carry its operating system in their heads.

- When you don’t know your rights, you can’t defend them.

- When you forget your history, you’re condemned to relive its worst chapters.

- When you can’t evaluate arguments independently, trace logical connections, or recognize manipulation, democracy becomes a word without meaning.

And there’s something else we’re losing — something harder to measure but equally vital to a functioning society.

Section 003

Emotional Debt

If the mind can incur debt, so can the heart. Alongside our intellectual deficit runs an emotional one: a growing intolerance of sitting with discomfort.

When confronted with criticism, the emotionally indebted don’t pause to process. They flee to TikTok, Instagram, X for relief. The algorithm obliges, on demand and at scale. The friction that once shaped character vanishes into a dopamine fog, where the emotionally indebted congregate to vent, scroll, or self-regulate until the pulse of discomfort fades.

I see this everywhere: young professionals, students, and most critically, new parents. I’ve watched caregivers in playgrounds, phone in hand, erupt in primal bursts at their children. These are reflexive releases with no resolution.

Neurophysiologists call this affective discharge: cortisol plunges, breathing steadies, the brain registers relief…and the lesson evaporates. Years of digital conditioning have trained the nervous system to seek instant release the moment pressure builds. The system resets, but the wiring stays the same — a coping loop of regulation without reflection.

Just as we must actively choose not to delegate our thinking, we must choose whether to outsource our feelings. If we won’t train our minds to solve problems, will we even learn to feel them?

Section 004

The Builder’s Discipline

Beyond finance, the people who understand debt most deeply are those who live and die by technical debt: the builders. My people.

Throughout my life, I’ve worked with them:

- scientists designing observatories that peer back to our universe’s creation

- astronauts training for missions everyone said were impossible

- engineers pushing materials beyond their known limits

Builders metabolize discomfort differently. They don’t flee from it, nor reach for digital or pharmaceutical coping mechanisms. They use it. Unsolved problems are fuel. Every 18-hour struggle session deposits cognitive capital. Failures that force founders back to first principles carve neural pathways no textbook or chatbot can replicate.

Technical debt actually teaches you the true costs of instant gratification. This debt always comes due. The code you ship in haste at 4 AM will break something six months later. The documentation you skip will haunt you next year when you can’t remember your own logic. You cannot negotiate with a failing system or scroll past a memory leak. The machine does not care about your feelings. It either works, or it doesn’t.

This brutal honesty shapes the builder’s mind into specific neural architecture:

- Working memory density. Holding and juggling multiple variables simultaneously without dropping one

- Prefrontal discipline. Governance of planning, impulse control, and the willingness to delay gratification comes from repeatedly choosing the hard but necessary solution

- Mental modeling. Rotating complex systems in your mind before they exist in reality

- Adaptive resilience. Converting every failure into data, every setback into strength

These are not genetically endowed personality traits. They’re biological adaptations to chosen difficulty. Convenience corrodes by removing the friction that builds these circuits.

I’ve seen it repeatedly throughout my career: when our backs were against the wall, we succeeded because our minds were conditioned by friction, not protected from it.

Today, at 85, I still often start with a pencil and blank paper. I’ll work late into the night with these “primitive” tools, visualizing complex systems in three dimensions and rotating them in my mind until I can feel every stress point and potential failure. The point is to ensure the architecture is sound before we start building. The software can validate what I’ve conceived, refine the mathematics, and prove the physics, but it can’t replace the deep knowing that comes from carrying entire systems in your head.

That intuition, earned through tens of thousands of hours of wrestling with impossibility using nothing but the brain, can’t be downloaded, bought, or prompted. It has to be built and rebuilt, problem after problem, failure by failure, year after year.

Section 005

When The Bill Comes Due

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Which way, America?

- Down one road lies the path of least resistance. At the end of this road, you’ll find convenience as the paramount virtue of our society. We feast at the slop trough, on fragments, instant answers, and pre-digested opinions until we forget how to think. This road ends where all dependencies do: helplessness. Ryan Duffy, our editor, already has a name for the destination — Slopocalypse.

- Down the other path, we harness the remarkable technology that is AI without surrendering our intellect. Those confident in their abilities use machines to enhance thinking, not replace it. But this confidence is earned through friction, failure, and the daily decision to think rather than merely prompt. This harder road leads toward hybrid intelligence, with the human mind and machine capabilities working in tandem to solve problems once deemed impossible.

Here’s the supreme irony: we built neural nets by borrowing metaphors from our own brains. Now our brains are at risk of quietly retraining on our neural nets’ model weights and the internet’s data distribution. Hebbian plasticity (neurons that fire together wire together) is still doing its ancient work, but we’re reinforcing shortcuts:

- Transactive memory off-loads facts to the cloud (digital amnesia)

- Heavy, habitual media-multitasking degrades sustained attention and task-switching control

- Chronic smartphone overuse is associated with structural changes in prefrontal circuitry that governs impulse control and planning.

If we’re not careful, the more our AIs model us, the more we’ll model them — until we can’t think past a prompt.

But the choice before us is not fundamentally technological. AI is a tool, and a supremely capable one at that. Banning it would be impossible and idiotic – like trying to prohibit mathematics or uninvent the wheel. The choice is about cognitive sovereignty: Do we own our thoughts or rent them? Do we remain sovereign beings, or do we become biological middleware between prompt and output?

The Way Forward

Cognitive sovereignty starts with small acts of resistance. Solve a problem without AI. Write a page or diagram by hand. Sit with frustration for five minutes before reaching for relief.

- For educators: Design for divergent thinking. Teach and cultivate AI literacy. Require synthesis, not regurgitation. Build metacognitive awareness — students should document and explain their thought process, not just provide an answer.

- Students & young adults: Practice interleaving (alternate between AI-assisted and unassisted work). Master a skill without digital help. Build semantic memory through spaced repetition. Read something daily that challenges your attention span.

- At work: Embrace and enforce time-boxed deep work. Solve a problem from start to finish without shortcuts. Challenge yourself, and present from only working memory once a month. Celebrate the struggle before the breakthrough.

- For parents: Let your kids be bored. Make them work through frustration. Think out loud so they see how problem-solving actually works.

- In life: Notice when you’re outsourcing your thinking — that moment when you reach for your phone instead of reasoning through something. Choose to re-engage. Remember things without looking them up. Have one daily conversation with no phones present.

Above all, recommit to the builder’s mindset. Celebrate discomfort as a crucible of growth, insist on long‑term thinking in a culture that values instant gratification, and use AI as a cognitive copilot that challenges you, rather than as a prosthetic autopilot that thinks for you.

We are not here to administer the last rites for deep thinking.

Per Aspera exists because we believe the future belongs to those who think for themselves. We’re gathering the builders who refuse to surrender their cognitive sovereignty, who will not go into that intellectually impoverished night.

By joining Per Aspera, if you’re signed up, you’ve willingly opted in to reading thousands of words of intellectually dense, long-form text each week. This is strength training for the mind, with a regimen grounded in rigorous neuroscience, advanced technology, physics, economics, and civilizational inquiry.

You are proof that acts of cognitive resistance are possible. You’ve chosen our countercultural programming in an era where popular culture has swung violently toward slop troughs (attention-hijacking, short-form media; constant dopamine-inducing systems; and empty-calorie content).

This ties directly to Per Aspera‘s mission. We’re a high-performance community for people doing great things. If our tribe agrees on one thing, it’s that the only way to achieve great things is through hardships. Hell, it’s literally in our name: Ad Astra Per Aspera — to the stars, through hardships.

You’ll need patience to work through failure, discipline to hold competing ideas in your head without reaching for the simple, and courage to stay lost until you find your way through. But the stars aren’t reached by comfort and convenience. They’re reached by those strong enough to endure the difficulty of the journey. To renew our identity as a nation of builders requires daily choices, thousands of small decisions to think rather than outsource, to struggle rather than surrender, to grow rather than atrophy. This is the path that belongs to all of us.

So I ask once more: Which way, America?

Slouching toward Slopocalypse, or striving for the stars?