Good morning, this is your captain, Ryan Duffy, speaking. Did you miss us yesterday? Thanks to all of you who reached out, wondering where their Monday Per Aspera was. We’re running an experiment this week (sending on Tuesday). We’ll be back in your inbox next Monday with regularly scheduled programming.

Today, we take on the topic of Intel and the prospect of building a leading-edge American foundry. Come for the story about Dan’s first time meeting Morris Chang, the legendary founder of TSMC. Stay for an overview of the hard path that lies ahead.

Before we go any further, the whole Per Aspera crew wants to thank you for being part of the American Renaissance in Hard Pursuits. Now, let’s dive in.

P.S. Were you forwarded this email? Subscribe here.

ONLY THE PARANOID SURVIVE

The world doesn't need another “Intel in trouble” autopsy. We wrote that story four years ago, and we were far from the first (or last) to do so. Today, the signs are everywhere: Intel is cutting 25,000 jobs this year and pulling the plug on marquee projects. Last year, it posted a staggering $18.8B loss, plus $2.9B in Q2. The vaunted 18A node hit a wall on yields, delaying flagship launches and effectively forcing a pivot to the upcoming 14A node. The company has cycled through four CEOs in seven years. Lip-Bu Tan, its latest leader installed in March, is fending off resignation calls from the White House and former board directors.

As Intel faces the proverbial fork in the road, the Western world is staring down a single point of failure: an earthquake, or invasion, that could threaten its entire technological foundation and industrial base, while wiping out trillions of economic value in a week.

How do we claw our way out of this one? To understand the real choices, let’s first start where the industry split.

THE BET TSMC MADE

In the early 1980s, the United States sold more than half the world’s chips and built more than a third of them. The giants of that era (Intel, Texas Instruments, Motorola) kept design and fabrication under one roof. The “fabless” model was a curiosity, if not a heresy: a pure-play foundry barely existed!

NASA operated a semiconductor facility for spacecraft electronics, pushing CMOS while gallium arsenide and other advanced materials came online. The country still built complex space systems from the transistor up.

We still sell most chips - we just don’t make ‘em. And therein lies the strategic risk.

Against this backdrop, our very own Dan (Goldin), then NASA administrator, flew to Taiwan at the invitation of Morris Chang. Chang, a former TI exec and founder of the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, Chang pitched Dan a radical idea for the time: TSMC, his firm, would design nothing. It would build everything, taking any customer’s designs that met its standards.

In the U.S., this ran against the grain of vertically integrated giants like Intel, where product and manufacturing were inseparable. In Hsinchu, walking the line with Morris Chang, Dan didn’t find a modest shop. He found the makings of a machine: fast turns from concept to wafer. Floor teams trained like craftsmen. Exhaustive process controls. Tooling pressing the frontier.

TSMC would become the high priest of horizontal specialization: By stripping away the distractions of product competition and pouring every ounce of capital and talent into becoming the world’s manufacturing “homeroom,” TSMC built a reinvestment and execution engine no integrated rival could match. That decisive commitment to the pure-play foundry model — free of conflicts and focused entirely on customer success — is the choice Intel has avoided for decades. And it’s the crux of the problem we need to solve now.

STRATEGIC AMNESIA, SEMICONDUCTOR EDITION

Intel spent the better part of two decades hollowing out its manufacturing edge through a familiar script. The center of gravity shifted from fabs to finance. Among the managerial ranks, engineers were shown the door and MBAs were ushered in.

As TSMC poured its free cash flow into process technology and scale, Intel optimized for financial engineering. Between 2001 and 2020, the company directed ~$128B toward stock buybacks. The opportunity cost is staggering: that money could have built several advanced-node fabs in the U.S., fully tooled and operational. At TSMC-style reinvestment rates, it would have bought Intel not just capacity but a seat at the leading edge.

The results are instructive: TSMC now holds ~90% of the world’s sub-7nm capacity. Intel, once the envy of the industry, finds itself years behind on process nodes and depends on others to manufacture its most advanced designs.

OPTIONS ON THE TABLE

At this point, Intel doesn’t lack options, but suffers from the wrong kind: partial moves, incremental pivots, and divestitures that don’t close the strategic gap.

If we’re serious about eliminating America’s single-point-of-failure in advanced chips, the menu boils down to a handful of real options, as Contrary Research laid out in its excellent, recent writeup on Intel (supplemented by turnaround plans floated from former Intel leaders in the last week):

Build a new national champion from scratch. Start a fresh, federally backed foundry and try to clone TSMC’s capability on U.S. soil. You’d need $100B+ and more than a decade of steady appropriations, multi‑year EUV and High‑NA tool lead times, a full domestic stack for gases, masks, photoresists, and a trained workforce measured in tens of thousands. It’s a clean narrative, but essentially a clean-sheet fantasy — and far too slow to matter.

“Just bring TSMC here.” TSMC’s Arizona fabs and Samsung’s Texas buildouts prove you can lease a little capacity. But you don’t get the crown jewels. Neither TSMC nor Samsung will transfer their best technology stateside. Taiwan and Korea will get the flagship nodes and hit mature yields on home turf first, and advanced packaging remains tethered to domestic fabs. In Taiwan especially, sacrificing the Silicon Shield is a political nonstarter (and, in fact, illegal). This path hedges: it buys (some) time and trims exposure, but it does not harden sovereignty and still leaves most leading capacity inside missile range of the PLA or Kim Jong Un.

Form a supply chain syndicate. This week, Craig Barrett, former CEO and board chairman of Intel, outlined a plan in Fortune: raise ~$40B from Intel’s biggest customers (OEMs, hyperscalers, and the defense primes) in exchange for equity, board-level oversight, and guaranteed supply. Under this program, these volume anchors would underwrite the expansion the foundry needs and align governance with delivery.

Split, spin, and segment. This path would have Intel sell off its product groups to focus on the foundry business. Four former Intel directors argued for exactly that in a rare joint statement to Fortune last week, warning that the company will retreat from manufacturing unless the fab business is separated and recapitalized on its own terms. The only way through, per this line of thinking, is a true separation of church and state, freeing Intel’s foundry business to attract outside customers who otherwise won’t trust their chip designs with a competitor.

INTEL’S LAST MISSION

We believe that Intel’s last mission is to transform itself from a conflicted conglomerate into America’s sovereign foundry. It’s the only company left with the physical scale, partial capability, and geographic position to give the United States a truly sovereign advanced fab. And it will not get there with an identity crisis. Divest distractions and conflicts, go all-in on foundry, and become the manufacturing homeroom for the West. That clarity of purpose would also make a supply-chain syndicate far more likely to succeed.

Critics have a fair case: you can’t conjure up TSMC’s culture, supplier web, or process dominance by industrial policy or subsidy alone. Intel must break habits of delay and inertia, and it must hit aggressive yield and process targets with relentless focus. Detractors warn of cronyism, misallocation of taxpayer funds, and legacy baggage. We can address this by making any federal money contingent on performance — released only when clear benchmarks are hit on yield, cycle time, node readiness, and on-shore packaging.

The reality remains: despite past missteps, Intel is the only American firm within striking distance of state-of-the-art logic manufacturing. It is the sole realistic candidate for a U.S.-controlled, leading-edge foundry at scale.

This path is hard and full of ways to fail. But we already tried the easy path. Look where it got us.

It’s time to choose the hard one — the path that builds, leads, and wins. The question left is: Do we have the will to win?

Catch your favorite Per Aspera duo 9th NASA Administrator Dan Goldin and Editor-in-Chief Ryan Duffy at the Space Economy Summit by Economist Impact, November 5–6, 2025 in Orlando. They'll join other industry experts to explore the next leap forward for space and the benefits to businesses here on Earth.

Register: Secure your spot here.

🚀 Stockpiling for Deterrence. Lockheed Martin and RTX have secured two major U.S. Air Force contracts totaling $7.8B, aimed at replenishing and expanding missile inventories amid growing global demand. Lockheed’s portion (~$4.3B) covers production of Joint Air‑to‑Surface Standoff Missiles (JASSM) and Long-Range Anti‑Ship Missiles (LRASM), including Foreign Military Sales to Finland, Japan, the Netherlands, and Poland. Meanwhile, RTX’s award of $3.5B represents the largest contract in the Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM) program’s history, delivering missiles and support to over a dozen allies including Israel, Taiwan, Ukraine, and the U.K.

PA Take: These firm fixed-price contracts signal a deliberate shift from reactive replenishment to strategic stockpiling, with an urgency unmistakeably fueled by real-world tensions. Now for the next test: can the primes deliver on schedule and cost?

⚫ Talent Mafias. Forward Deployed Venture Capital (FDVC) has raised their Fund II — a $45 million defense and security fund, raised from 150 current and former employees of tech companies like Palantir Technologies, SpaceX, and Anduril Industries, along with institutional backing from Bain Capital Ventures and other unnamed firms. Founded three years ago by General Partner Mark Scianna, a former Palantir forward-deployed engineer who built software for the U.S. Army and Marines for over a decade, the FDVC is the “first call” for startups in defense, industrials, and other critical industries where software and AI remain under-adopted.

PA Take: As Scianna has stated, FDVC invests in “talent mafias” 👇.

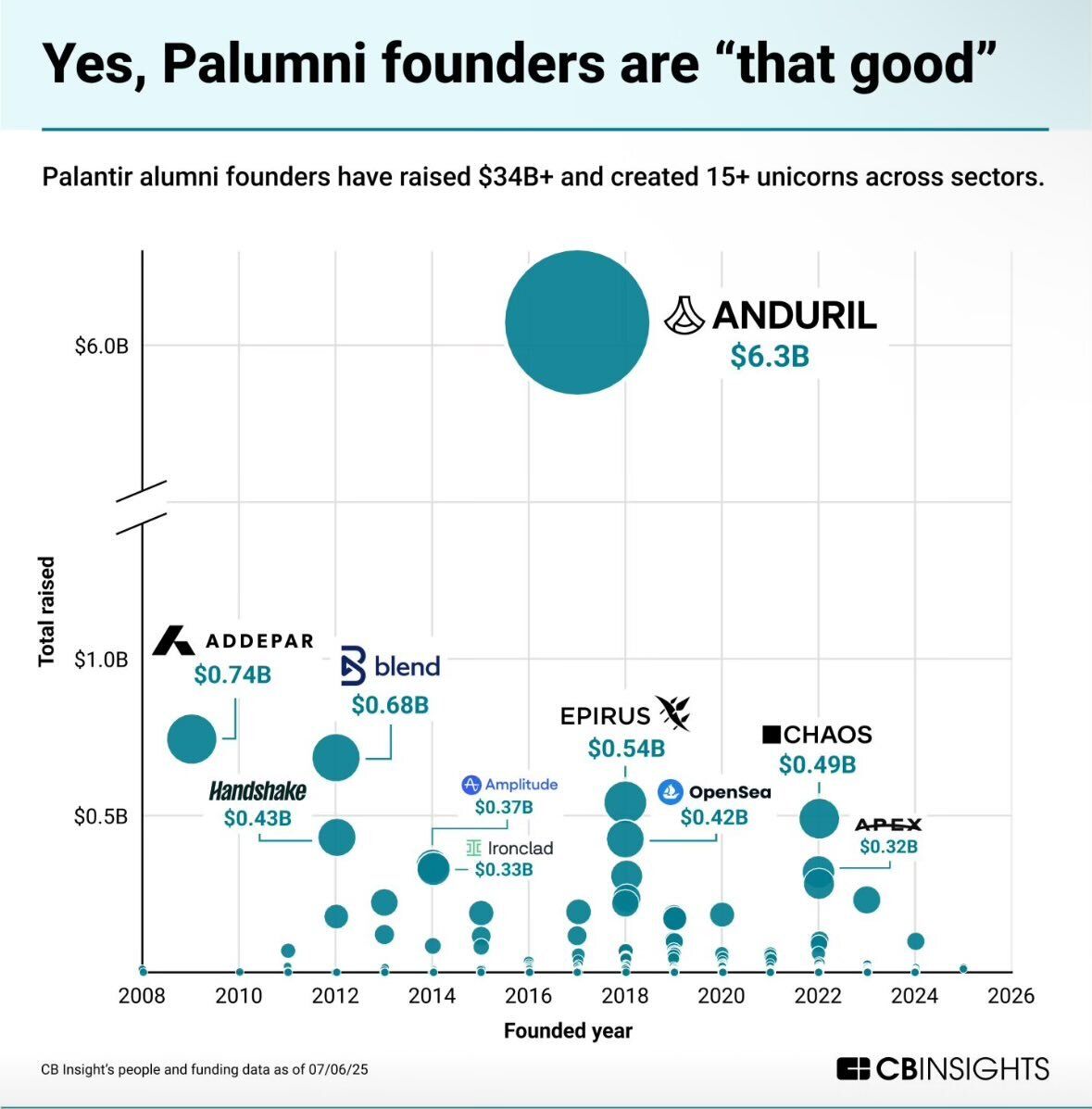

The “talent mafia” thesis points to a structural evolution in VC: the consolidation of influence, capital, and execution power within a distinct founder class. Alumni from Palantir, Anduril, and SpaceX have proven they can repeatedly and reliably generate multi-billion-dollar outcomes, raising $34B+ and building 15+ unicorns.

These networks have shared cultures, operating playbooks, and high-trust relationships, reducing both capital risk and execution time. FDVC’s Fund II manifests this shift well, via capital that flows straight to operators, skips traditional VC filters, and ultimately compresses the path from concept to fielded capability.

⚡Sovereign Compute. Armada, an SF-based “hyperscaler for the edge,” has raised $131M in a round led by Pinegrove, Veriten, and Glade Brook, with backing from Founders Fund, Lux Capital, Shield Capital, Microsoft’s M12, and others. The company has also announced the launch of Leviathan, a megawatt-scale modular AI data center delivering 10× the compute of its Triton model. Ruggedized and liquid-cooled, each Leviathan can be stood up within weeks in remote or contested areas, running on power sources like natural gas or solar. As the largest node in Armada’s Galleon lineup, Leviathan could help push AI training and inference to the edge.

PA Take: First, we like the naval-inspired naming schemes. Second, Armada’s products attack two AI infrastructure chokepoints (compute and power) by packaging MW-scale GPU clusters into movable modules that are deployable wherever cheap energy, data collection, and analysis needs optimally converge. For hyperscalers, this could complement rather than compete, filling edge applications that more centralized infrastructure can’t economically touch. For energy providers, this could be a golden ticket, helping monetize otherwise stranded or surplus power.

What’d we miss? Have something others participating in the Renaissance should know? Hit reply and drop us a line at [email protected].