Introduction

Foreword

There is an old adage in the energy business: “fusion energy has been 30 years away, for the last 60 years, and always will be.” This line is so common you can find it on Wikipedia.

We have heard the joke for most of our careers, but we hear it less and less these days.

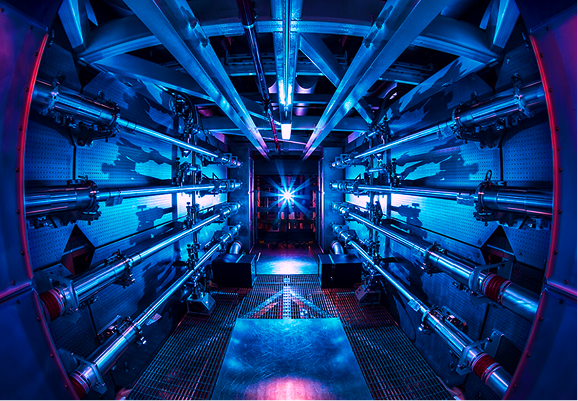

One of us (Ed Moses) led the design, build, commissioning, and early operation of the National Ignition Facility (NIF). A few years ago, NIF became the first machine in human history to demonstrate that controlled fusion can produce more energy than it consumes. It achieved net physics energy gain in December 2022. This has since been repeated many times, with increasing performance, proving the fundamental physics of laser fusion.

But we are not writing this to look back.

Rather, we are here today to say: laser fusion is on the cusp of commercialization and cost-effective production of energy that’s carbon-free, safe, and deployable wherever it’s needed most. And while laser-driven fusion is the first to cross the existential barrier to commercialization, hopefully it will not be the last.

Section 001

The Demand Side

The defining story of fusion in 2025 and 2026 is coming from the demand side.

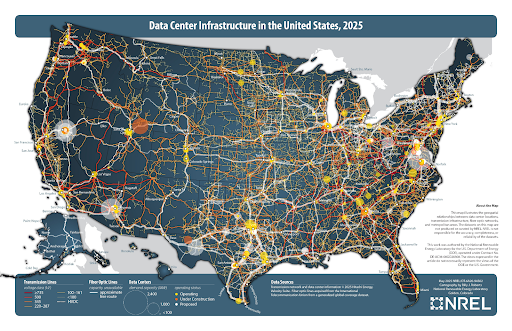

America is building the most power-hungry industrial base in its history, on a grid whose basic architecture dates back to the Eisenhower era. We’ve patched, extended, and upgraded it over the years, but never rebuilt for what’s coming. Datacenters alone are tracking to take ~10% share of U.S. electricity within the next 5-10 years, with credible scenarios pushing higher as AI deployments scale. At the same time, we are reindustrializing: chip fabs, defense systems, electrified transport, and advanced factories are landing and waiting to tie on to the grid.

There’s an irony here.

The technologies driving this demand are themselves children of the electrical revolution. Maxwell’s equations gave us electromagnetism. Quantum mechanics gave us semiconductors. Information theory gave us computing. A century of physics, technology, and investment built these industries. Now those same industries need more electricity than the grid that enabled them can provide. And it’s not only computing, industry, or traditional users driving this growth. Our future economy will need clean commodities, which all require vast amounts of low-carbon power to produce hydrogen, ammonia, synthetic fuels, cement, and the like.

This calls for nothing less than a new revolution in how we produce power.

To make a long story short: energy demands are exponentiating in every direction and the capacity to move power to where it is needed is not.

Our grid is aging, overloaded, and misaligned with where, how, and what industry wants to build. Permitting a major transmission line takes longer than the Apollo program. We see power demand hotspots around the nations including in the Mid-Atlantic, Texas, the Midwest, the Northeast, the West. Too often, the places that need power most are those who are least served with today’s grid and energy production paradigms.

This is the backdrop against which fusion has gone from ‘someday, maybe’ to ‘soon, definitely.’ The stars, pardon the pun, are finally aligning for this technology, with proof of ignition, billions in private capital, an inflow of elite talent who see great potential in fusion, and an effectively insatiable orderbook for anyone who can actually deliver.

So, how do we definitively retire the “30 years away” punchline?

Section 002

A Quick Primer on Fission & Fusion

Fission splits heavy atoms (uranium, thorium, plutonium) and releases energy. It powers today’s nuclear plants, aircraft carriers, and submarines.

Fusion does the opposite, combining light atoms (hydrogen isotopes) under extreme heat and pressure. It is the very same nuclear process that powers every star in the cosmos.

Fission has its challenges: fuel production, long-lived radioactive waste, meltdown risk, and a public that still carries the memories of Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima, even as public opinion has recently warmed.

Fusion’s challenge is different: proving it can work commercially and at grid scale. Achieving ignition using lasers (the barrier that NIF crossed) was a turning point. That achievement shifts fusion’s core challenge. It is now an engineering challenge, a manufacturing challenge, a policy challenge, and a capital challenge. These are hard, but they are tractable. It’s why I (Ed) waited for the right time to found my fusion company, Longview Fusion Energy Systems, which is using the exact same method that was proven at NIF.

Section 003

The Promise of Fusion

Assume, for a moment, that engineering and technology can meet the physics requirements. Fusion offers a profile that no other energy, let alone clean energy source can match:

- Carbon-free primary power: large, steady, CO₂-free output designed to carry a major share of the load, not just fill gaps.

- Economics that improve at scale: abundant fuel, high capacity factors, and standardized plant designs so that the cost per kilowatt-hour falls as fleets or fusion engines are deployed.

- Industrial-grade output: sized to GW-scale datacenters, population centers, major defense installations, matching the demands of a fully electrified economy.

- Compact and local: high output from a small footprint, so power can sit close to where it is used rather than hanging off long, fragile transmission lines.

- Future-compatibility: a platform that can integrate better materials, advanced fuels, and new applications over time without redesigning the entire energy system.

Fusion is the key technology capable of removing the long-run ceiling on clean firm power. It ensures that AI, electrification of transportation and heat, and continued industrial expansion do not run into absolute limits on land, emissions, or societal acceptance.

Location, Location, Location

Fusion changes the calculus on where power can go.

At commercial scale, fusion offers a fundamentally different risk profile than fission: no chain reactions, no meltdown mode, no long-lived waste, and no proliferation concerns in the fuel cycle. Unlike renewables, it is compact, dispatchable, and firm baseload power, not intermittent generation, and, unlike hydrocarbons, fusion produces zero emissions.

Fusion can operate as “behind-the-meter” generation (power produced where it is consumed). Hyperscalers and government customers are especially interested in such arrangements. But since it can also connect to the grid and supply urban centers, fusion can serve a crucial role both as for supplying electrical power and a stabilizing force for our energy system, by providing secure, clean, abundant energy without waiting for grid improvements, and giving renewable-heavy regions a firm, dispatchable backstop (when the alternative would be overbuilding batteries and peaker gas plants).

Fusion’s dual-hat role – serving as both a self-contained, behind-the-meter solution and able to power and stabilize the grid – makes it the most compelling power source for the future, provided it can reach commercial viability. Which brings us to our next section…

Section 004

The Commercial Moment

Fusion has lived in national labs for decades. We should know: one of us ran one of those labs; the other spent years working with and inside them. While these long-range programs were the essential birthplace of the technology, and will continue to advance the fundamental science, they don’t build commercial power plants. That job belongs to the private sector.

For a long time, industry couldn’t answer a simple question for fusion: What is the path to grid power? Today, we can. The science is proven, the need is urgent, and for the first time, the path to commercial, grid-scale power is clear.

Ignition

The NIF achievement moved us closer toward commercialization of Inertial Confinement Fusion (ICF) technology. In our view, this is ready for primetime, and it’s what we at Longview are pursuing. While other approaches using magnetic confinement are also making strides, NIF’s ignition success provides the fundamental validation that the energy barrier has been crossed. And, for the first time, the field has a proven physical foundation and a credible engineering roadmap.

Capital

Over the last five years, nearly $10B of private capital has flowed into fusion companies, with $2.6B raised in the past year alone. Investors are showing growing confidence in fusion, its technological progress, and rapidly developing talent ecosystem and supply chain. Political capital is also stacking up: over the last year, governments in Japan, Germany, China, the U.K., South Korea, Canada, the EU, and the United States have passed policies supportive of fusion power. Public funding has grown 84% year-on-year, from $360M to $800M.

Competition

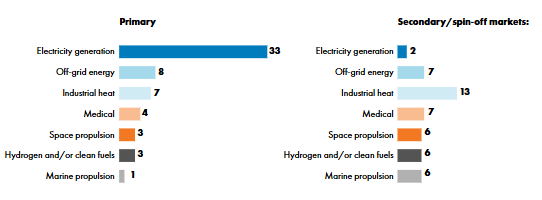

U.S. companies are pursuing a wide range of technically differentiated paths to power plant-scale machines. Each is building a different machine with different physics: lasers, stellarators, tokamaks, z-pinches, field-reversed configurations, and so on. This diversity makes the fusion community even stronger and accelerates our collective learning. We all have our own unique theses and timelines, but by and large, our teams are buoyed by an increasingly sophisticated investor base, with teams built by former national lab leaders, and talent matriculating from the optics, semiconductor, magnet, laser, power, and advanced manufacturing sectors.

A Worthy Analogy

Fusion today looks less like a distant science project and more like the early days of Silicon Valley or commercial space. The SpaceX comparison in deep tech is often overused, but it works well in this context: investors are backing competing business models and technical bets, generally based on government R&D investments, while startups build successively larger machines, iterate hardware in the real world, and learn by doing. Our goal is to measure success through power purchase agreements and grid-relevant plants that can solve real-world problems – not only scientific papers and citations.

Fusion has not yet had its “Falcon moment,” the demonstration that proved a private space company can do what only governments could do before, and do it faster, better, and cheaper. But, as an industry, we are operating as though it is a matter of when, not if.

Section 005

How Can Washington Help?

Other advanced economies see the same thing we are seeing: soaring AI and data demand, electrified transportation and militaries, fragile grids, climate constraints, and lingering public skepticism of big energy projects and, in particular, nuclear energy. China and Europe are already putting substantial state resources behind private players and positioning fusion as a key pillar of their long-range energy portfolio.

If fusion is to matter on the timescale of the current industrial and security challenges of our day, the U.S. cannot afford to treat it as a “30 years away” problem with purely government-run R&D programs. We just do not have that luxury, nor the time.

We believe that the right model for this moment is one that is commercially led and publicly supported. The action plan should be to:

- Leverage industry speed and capital (and not replace them – accelerate and amplify them!)

- Lean on government’s strengths: technical expertise, unique facilities, and early adoption.

- Align around hard milestones for demonstration plants, then First-of-a-Kind (FOAK) power plant commercial deployments – not open-ended horizons. This will show who is ready.

- Educate the American public on the value of fusion, for their own lives, for their children’s lives, and for the health and resilience of the planet.

On the ground, this means:

- Co-funding with purpose. Pilot plants that serve national security loads, critical infrastructure, or federal facilities. We must solve real problems.

- Licensing fit for the risk. Streamlined, fit-for-purpose, fusion-specific pathways that recognize its distinct risk profile compared to fission. The NRC and Congress have started this work; 2026 needs to see it finished.

- Coordinated siting. DOE, DOW, Department of Commerce and State, NRC (or successor frameworks), and state/local governments should be actively talking to each other, so that first deployments land with maximum impact.

Done right, the federal government becomes not the sole architect and operator of fusion, but an enabler of the private sector and an accelerator of deployment.

Section 006

What 2026 Needs to Deliver

Fusion is famously hard. It sits at the intersection of physics, engineering, economics, and hardware. It punishes wishful thinking and breaks the heart of blind optimists. And failing to respect fusion’s complexity and challenges could lead to disappointment again. If we are being honest, grid-competitive fusion electricity is not a 2026 story. But the industry is racing to ensure that it is a 2030s story. If we remain ruthlessly disciplined, it will be a story with a deserved and historic ending.

The window for American leadership is real, but it will not stay open forever.

Follow the trend lines for AI, electrification, and reindustrialization far enough, and barring aggressive intervention, you are bound to hit a wall. There is a ceiling on how much diffuse, intermittent power a modern industrial superpower can absorb. And as we’ve seen, silicon efficiency gains don’t dampen our inference appetite – they simply induce more demand. The usual answers of more renewables or Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) in every subdivision, fail the test of scale and often devolve into permitting conflicts, local opposition, and hard geographical constraints.

So, we look to the stars…

If we want an economy in the 2030s that succeeds in meeting its potential, the solution is simple: Bring the stars to us. Master the physics of the sun right here on Earth, and deploy a source with the power density of a star.

Though next year will not be the moment commercial fusion plants land, it will be when we seriously enter into the design of the grid and gigaprojects of the 2030s. We’re in the early innings of the largest infrastructure upgrade since Eisenhower built the highways, with hundreds of billions of dollars flowing into the system.

The regulatory pathways, siting decisions, and pilot programs pursued in the next 24–36 months will determine whether fusion is a valid option when the power crunch reaches a breaking point, or if we are forced to lock in a future of more of the same — critical gear shortage, gas pipelines, and coal trains. Renewables will be essential, but they need a dispatchable power partner to carry the load when the sun is not shining and the wind is not blowing.

If the U.S. blinks, and we treat fusion as a 2050 science project while near-peer competitors see it as a 2030 industrial strategy, we will end up buying the fusion engines of our future economy from them, rather than selling fusion power to them. Now is the time to act.