The China shock(s): In late 2024, China fired a warning shot, abruptly announcing a ban on exports of several unpronounceable yet indispensable minerals. In the months to come, germanium and gallium spot prices went vertical as American corporations scrambled to bypass the ban and buy through third-parties in Thailand and Mexico. Alas, it was only the opening gambit.

In April 2025, hours after the White House imposed a new round of 25% tariffs on China, Beijing announced new export controls on seven critical rare earth elements. The next month, Ford’s Chicago assembly plant, 3,600 workers strong, went dark for a week, halting Explorer production for want of neodymium magnets. Ford boss Jim Farley called it a “hand-to-mouth” supply struggle. A couple weeks later, Suzuki became the first Japanese OEM to buckle, suspending Swift production at its Sagara plant due to rare-earth component shortages.

By June, European plants faced partial shutdowns. A German battery manufacturer scrambled to pass on antimony prices that had quadrupled to its customers, while an Indian automaker warned of a “zero month” for EV production. All the while, the Pentagon watched as contractors struggled to secure the dysprosium and terbium critical to actuators and sensor packages.

In mid-July, Washington and Beijing brokered a begrudging truce: China lifted some rare earth and magnet quotas, but only in exchange for U.S. concessions resuming Nvidia H20 AI chip shipments to the mainland. The immediate crisis had passed, but the message was unmistakeable: America’s industrial might was hostage to decisions made 7,000 miles away.

No Minerals, No Momentum?

The materials at the center of this skirmish are part of a broader class of “critical minerals” underpinning modern industry. The U.S. government’s official list runs 50 minerals deep, essentially a menu of elements without which high-tech economies cannot function.

Lately, headlines have focused on the 17 Rare Earth Elements (REEs). While they sound exotic, they are actually abundant in the Earth’s crust — just rarely found in concentrated deposits that can be economically mined. So, their functional scarcity is driven by geopolitics, refining capacity, and tribal knowledge.

To varying degrees, these elemental clusters underwrite every growth thesis in the American economy:

- Nd–Pr magnets — torque source for EV drive units, industrial robots, wind-turbine generators, and drone rotors; also the core actuator material in precision-guided munitions.

- Dy–Tb modifiers — high-temperature dopants that keep those magnets functional above 150°C in jet engines, hypersonic control surfaces, and other extreme-heat platforms.

- Li + Co cathodes — high-density, long-cycle storage chemistry now deployable at scale for electric vehicles, consumer electronics, and long-duration grid batteries.

- Ga + Ge semiconductors — wide-bandgap and III-V devices (GaN, GaAs, Ge) essential for 5G/6G radios, radar, satellite solar arrays, laser diodes, and high-efficiency power electronics in datacenters and EV inverters.

Atomic Dependence: The Current Account

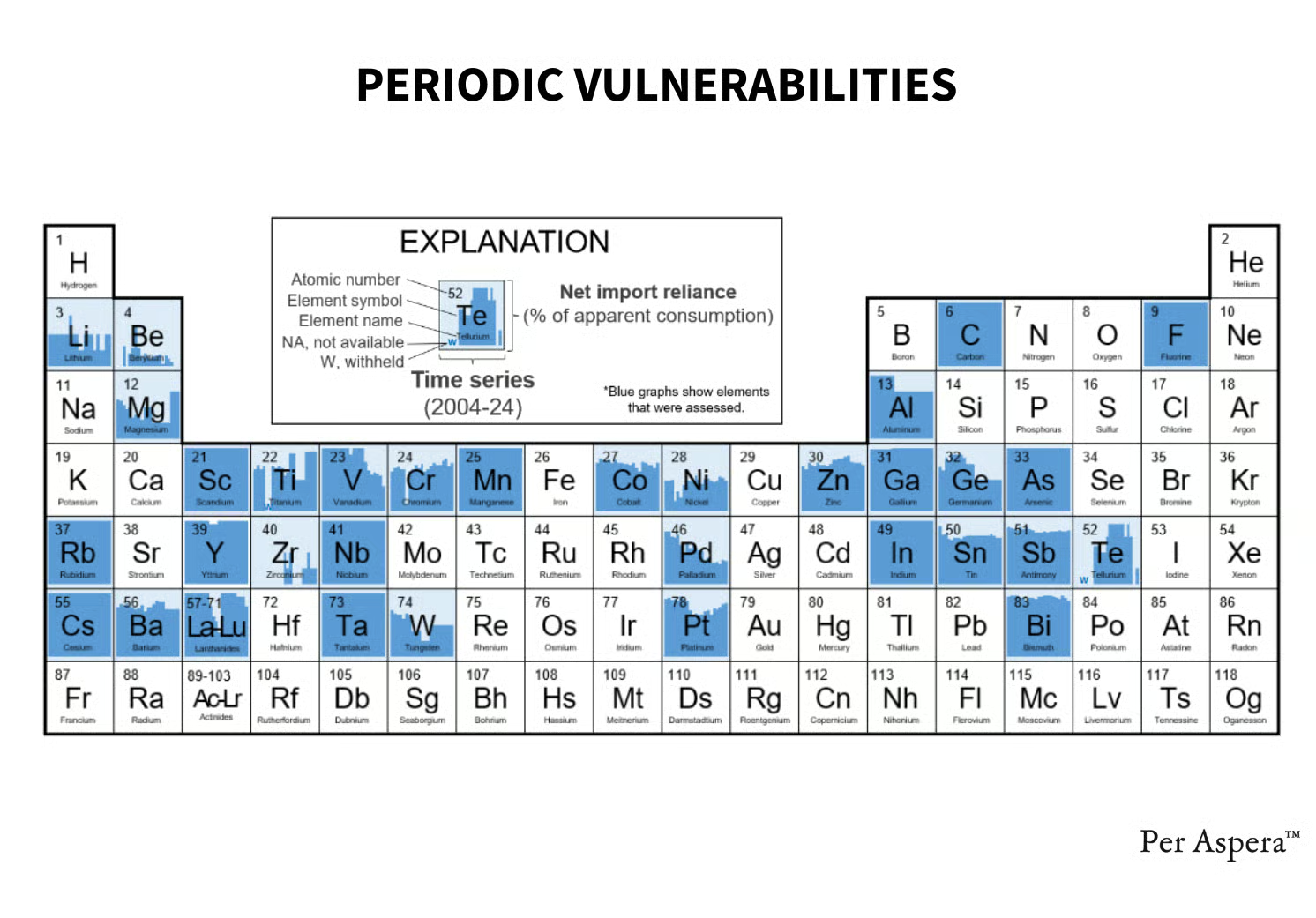

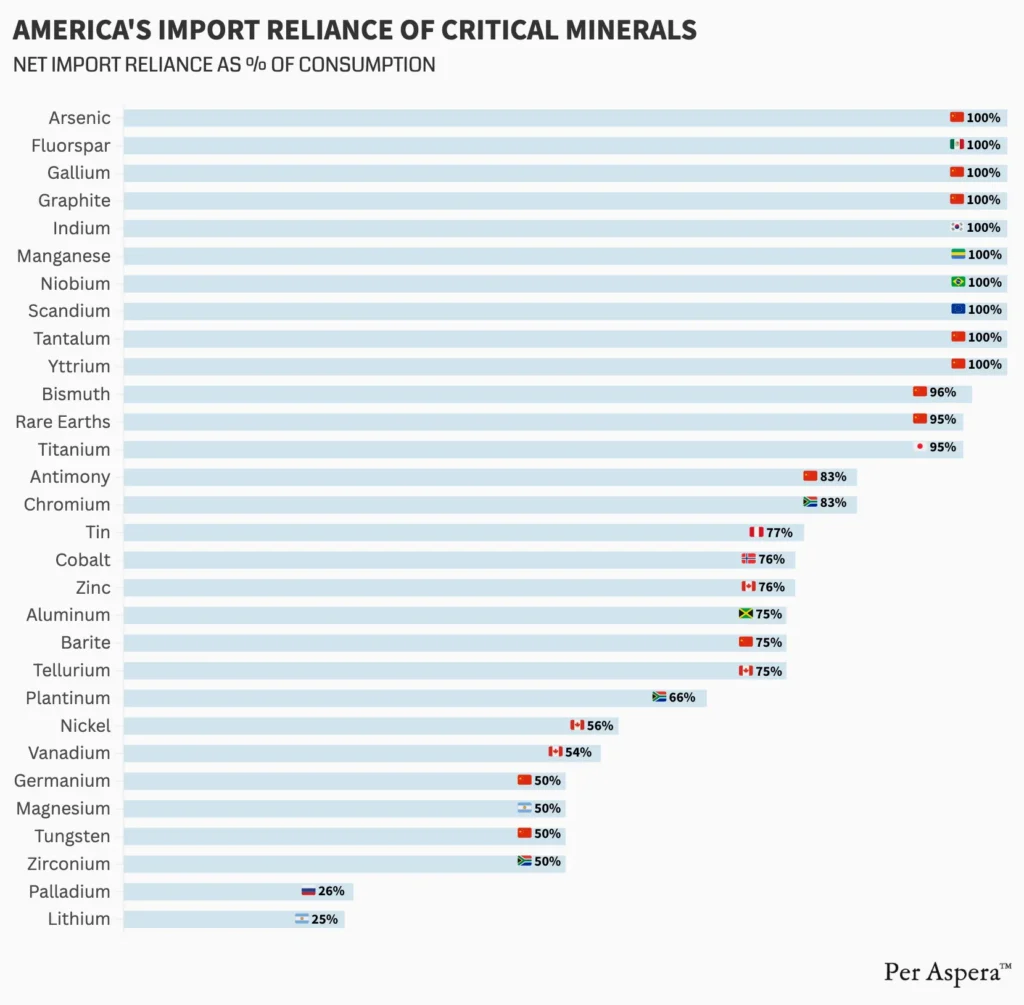

Of the 50 critical minerals, the U.S. imports 100% of 12 and more than 50% of 31. REEs are the most strategically fragile slice of that ledger: Light REEs (La–Nd) can be mined in California or Australia, but the heavy REEs (Dy–Tb, Ho–Lu) that harden magnets above 150°C come almost entirely from ionic-clay deposits in southern China and northern Myanmar.

Still, missing from this accounting is the step that converts rock into leverage. China controls ~85% of global separation capacity, the chemical circuits that turn mixed concentrate into individual oxides, and over 90% of finished-magnet production. The most critical chokepoint, therefore, is not geological but midstream, in processing and magnet pressing.

Mountain Pass: A Metaphor in the Mojave

From the 1960s through the ‘80s, California’s Mountain Pass mine pumped out 70% of the world’s light rare-earth oxides: the neodymium, samarium, and europium that lit up color TVs and guided Cold-War weapons. America sold oxides much the way Saudi Arabia sold oil.

“The Middle East has oil; China has rare earths.”

—Deng Xiaoping, 1992

Then, two curves crossed in the early ‘90s. Stricter U.S. environmental rules and rising labor costs coincided with China declaring REEs a “strategic resource.” The ascendant industrial power aimed not to compete, but conquer. State miners operated with zero-return requirements while enjoying 13% VAT export rebates. In the late ‘90s, Chinese state-backed firms acquired GM’s Magnequench, redomiciling America’s premier magnet technology to Tianjin.

Meanwhile, Mountain Pass bled cash, suffered spills, and shuttered in 2002. A $1.7B private equity reboot began in 2008, just in time for Beijing’s next move: restrict exports in 2010, spike NdPr oxide to $340/kg the next year, coax fresh Western investment, then crash the price back to $60 by 2012–13. Mountain Pass’s operators filed for bankruptcy in 2015.

Two years later, MP Materials acquired the site and resumed operations in 2018. It kept shipping concentrate to China for processing until this year, when it cut exports and the Pentagon stepped in with a 15% equity stake and a $110/kg floor contract. MP’s Fort Worth, TX magnet plant came online this year, with nameplate capacity targeting 10,000 t/yr by 2028.

The story of Mountain Pass is one of both A) strategic amnesia, and B) strategic reawakening, as Washington rouses itself from a protracted industrial sleepwalk.

America’s Awakening (and the Open Holes)

The White House has launched the most aggressive domestic minerals campaign since World War II; the Defense Production Act is back in play; Department of Energy loans are seeding battery-material plants from Nevada brine to upstate-New York cathodes. Task forces from Washington to Wyoming are dusting off forgotten deposits in Idaho, Quebec, and the Carolinas, while partnership pacts with Canberra, Ottawa, Tokyo, and Brussels aim to drive processing capacity out of Beijing’s orbit.

Useful…but partial. After scraping 50+ Congressional testimonies, agency reports, and think-tank memos, we found that more than four-fifths of all recommendations converge on three comfort blankets: 1) streamlined permitting, 2) allied partnerships, and 3) strategic stockpiling.

Credit for momentum, but let’s think through this in first principles. Per Aspera analyzes the mineral question through the lens of unit prices, calendar time, and externalities. And these are the facts: the mid-stream stack is still offshore; China can dump oxide to $35–60/kg as soon as Western financing turns shovels; and rare-earth separation remains one of the dirtiest processes known to industry, generating up to 10 tons of radioactive tailings for every ton of heavy-REE oxide pulled from the earth.

We see three strategic “doors,” each defined by the same first-principles yardsticks: unit price, calendar time, and externalities.

001 // Door A: Full-Stack, Capex-Maxxed Rebuild of the Entire Mining Value Chain. Mine, separate, alloy, and press magnets on American or Allied soil. It means solvent-extraction tanks, high-vacuum furnaces, and tailings ponds in somebody’s congressional district. The upside is absolute supply sovereignty; the downside is decades of building, $100–200B in potential outlays; and radioactive waste measured in railcars. Plus, there’s the question of human capital: U.S. universities graduated just 312 mining engineers in 2023, which is smaller than the UT Austin Longhorn marching band.

002 // Door B: Technology Leapfrogging to Rare-Earth-Light Magnets and Substitutes. Trade extraction risk for materials science, by bankrolling next-gen chemistries (Fe-N, Mn-AI-C, grain-boundary-diffused light-REE alloys) that reduce dependency on China-controlled heavy elements. A flagship example: Niron Magnetics, whose Sartell, Minnesota plant is targeting 1,500 t/yr of iron nitride magnets by 2027 (entirely rare earth-free, with zero dysprosium content). Could a modest national effort ($5-10B) help scale similar lines to multi-kt output inside a decade? Upside: dysprosium demand falls 90%, neodymium by a third, and the pollution profile falls to that of a modern still mill. Downside: coercivity and corrosion barriers still loom, motors must be re-qualified, and physics (not capital) sets the schedule. Door B could cost a fraction of Door A and trigger far less environmental blowback, but success hangs on materials performance, and still requires a reliable light-REE feedstock until substitutes catch up.

003 // Door C: Off-Planet & Offshore Hedging: Lunar Regolith, Asteroid Ores, and Friendly-Nation Refineries. Shift the dirtiest chemistry and geopolitical chokepoint off the board, either by going up (space) or out (friendshoring). In one direction, Artemis-era logistics open a path to lunar regolith rich in REE-bearing glass and asteroid ventures chase REEs in places where grades rival Earth’s best. On the other track, Australia, Canada, and South Korea court U.S. capital to fast-track heavy-REE separation plants on their soil (where pollution rules are stricter and cleaner processing could come standard, even if it means paying extra to do it right). The catch: the premium cost, logistics, and timelines for allied plants to come online at scale. And the off-planet route is still a decadal adventure in speculative engineering. Door C is a hedging strategy: slow and somewhat costly, but potentially essential insurance if other doors jam or adversaries shift from dumping to blockade.

What Happens Next?

Mineral sovereignty won’t be won by a single press release, policy memo, or Per Aspera Field Note. Each door carries its tradeoffs in dollars, years, and liabilities; none closes without something else giving way. This fall, we’ll publish an Antimemo that lays these choices and costs bare: an empirical, systems-level dive into the chemistry, cash flows, and geopolitical gambits that shape America’s mineral future. If you’re building, funding, procuring, or crafting policy in this arena — and you have data, concerns, or ideas — get in touch. The next export ban won’t wait for us to dither.