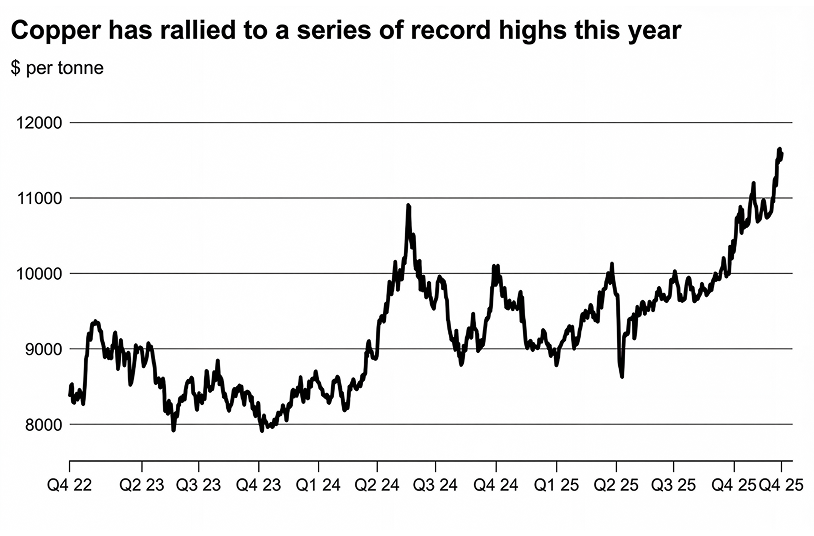

Without copper, you cannot electrify America, and without electrification, you do not have an AI supercycle:

- Datacenters call for 20-40 tons of copper per MW of capacity.

- EVs use 2-4x more copper than internal combustion engine vehicles.

- For grid expansion, for charging infrastructure, for transformers….copper is the common denominator.

For today’s big question, we ask: Why are we concentrating nearly $50B of copper investment in two of our most water-stressed states?

Copper carries the current

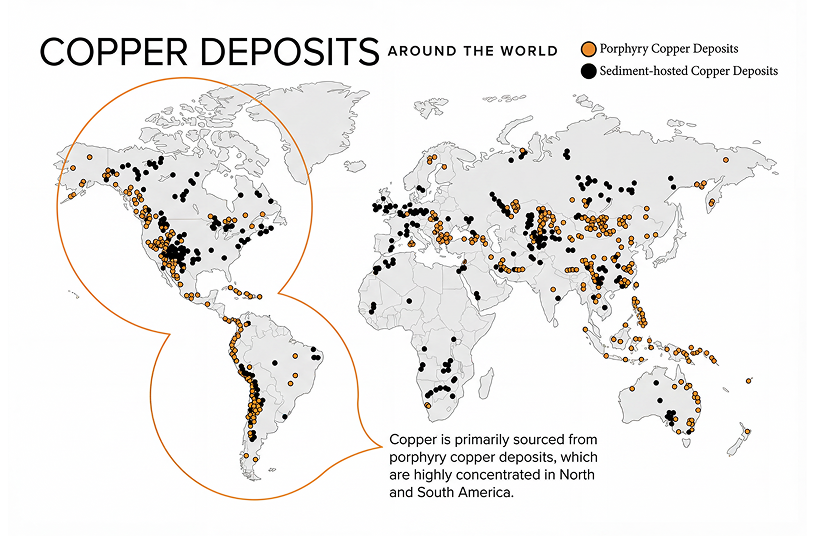

Copper is the second-best electrical conductor on Earth (after silver, which costs 80x more). Fortunately, America is endowed with nearly 50M tons (50,000 kt) of copper, which is ~15% more than China. We produce ~1,700 kt of copper content annually: ~1,100 kt from domestic mine production, and recover ~720 kt from scrap. On paper, this should be enough!

But sourcing copper, whether from mines or scrap yards, is only half the job. Ore must be smelted into crude copper, then refined into pure metal. Because we lack the processing capacity to refine all of our domestic copper ourselves, we export 325 kt of concentrate and net exports of 518 kt of scrap each year. Then we turn around and import 720 kt of refined copper to meet our 1,600 kt demand.

In essence, we are paying to move rocks across the ocean twice.

How we got here

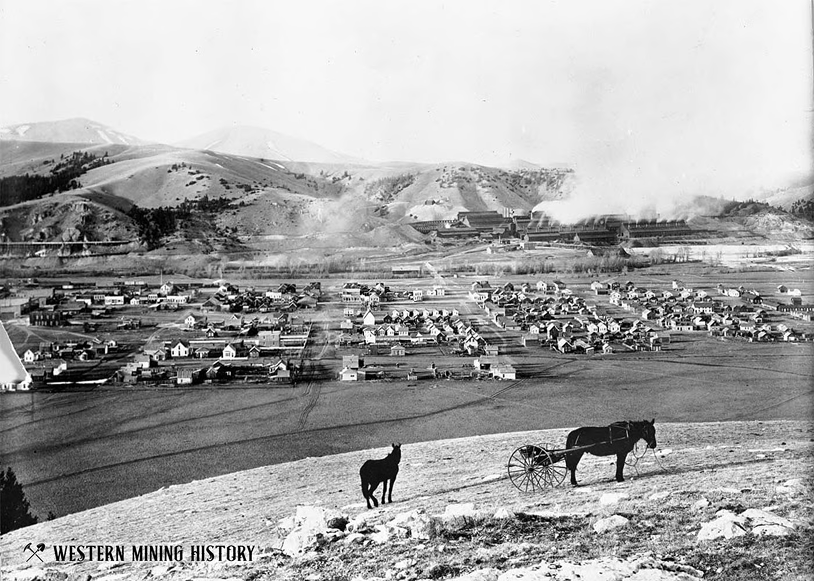

In 1980, we had 16 primary copper smelters producing nearly 1,400 kt annually. As regulations tightened, operators faced a choice: spend billions retrofitting facilities to get compliant, or ship the concentrate overseas. And so began the mass extinction event for America’s primary smelters, leaving us with two survivors: Miami in Arizona, built in 1915, and Kennecott in Utah, which opened in 1995.

There was good reason for those tightened regulations. Silent Spring awakened the country to industrial pollution in the ‘60s, with the Clean Air and Water Acts passing in 1970 and ‘72. And smelting is where the environmental problems concentrate: sulfur dioxide that causes acid rain, sulfuric acid from refining, enormous water volumes contaminated with heavy metals. The communities near these plants — Anaconda, Hayden, El Paso — bore the costs in poisoned soil and elevated cancer rates.

Less weary of caustic byproducts, an ascendant China made the opposite bet, building 97% of all new global smelter capacity over the past two decades. Today, it processes 45% of global refined copper with more smelting capacity than everyone else combined.

The environmental concerns were real, and they remain real. Smelting copper produces toxic waste that has to go somewhere. But the result of us not accounting for this externality — or innovating around it — is that we’re now dependent on China for processing capacity we used to have ourselves.

We’re stuck in a bind.

The clean processing technologies everyone talks about — scrubbers, closed-loop water treatment, electrochemical processes — aren’t ready for primetime.

- DOE has funded this work for years, but it’s not commercially proven at the scale EPA requires.

- Industry estimates put deployment four to six years out, if everything goes right.

And so our dependency gets more acute by the day. We need more processing capacity, but we can’t build it the old way…and the new way isn’t ready yet.

What we are doing is investing tens of billions into new copper mining projects.

The water paradox

Two of the states receiving the most investment are already rationing water:

- The Copper State (yes, this is the unofficial nickname of Arizona) ranks as the nation’s most water-stressed state.

- Neighboring Nevada faces similarly acute water stress from the same Colorado River Basin constraints and groundwater depletion.

We’re pouring capital into pulling more rock out of the ground — in the most water-stressed states in the country — while doing almost nothing to process it domestically.

The mines have to be where the ore is, because, well, you can’t move a copper deposit. But smelters don’t need to be next to the mine site. Today, the two are often thousands of miles apart — concentrate departs Arizona by rail for a port, crosses the Pacific for processing, and comes home as imported, refined copper.

The question we’re asking is not whether to ship concentrate, but where.

Per Aspera’s modest proposal

Sitting on the Great Lakes, with 20% of the world’s fresh surface water, Michigan has got the goods. Not only does it have the water, it has:

- Rail connecting to the Midwest industrial base

- A workforce that’s been building heavy things for a century

- Port access to the Atlantic via the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway

The Ohio Valley offers the same via the Ohio River system — Kentucky is already attracting big battery plants for exactly these reasons. We don’t even need to limit this to the Lower 48: Alaska has its own massive mineral deposits, 40% of America’s freshwater, and deepwater port access in areas far from sensitive ecosystems.

Why this keeps happening

When you see it enough times over enough cycles, you start to notice this pattern: A project will get announced in a water-stressed area. Then, it will stall, as water rights are contested. Permitting drags on for years, environmental reviews proliferate, and local opposition hardens as communities grow increasingly recalitrant against the notion of giving up their scarcest resource. (Can anyone think of any other class of megaprojects that are currently facing the same dilemma???)

The Great Lakes region has the water, infrastructure, and workforce, but it’s received almost no critical minerals processing investment. I don’t fully understand why. Maybe it’s the assumption that smelters need to be near mines. Maybe it’s regulatory uncertainty in the Midwest. Maybe it’s just inertia: this is where copper projects have always been, so this is where they continue to be.

We need to dispense with conventional thinking to work our way out of this one. We have enormous demand for this resource right now.

The mining investment pipeline is full — Resolution Copper ($8B+), Hudbay’s Copper World ($1.7B), the Bagdad expansion, Florence, Cactus. Comparatively few dollars are going toward processing, despite our ~700-800 kt gap. It’s time to start getting a bit more creative with where we stand up the next generation of smelters. Because we do need a next generation.

If we, as suppliers, put capacity in places where water isn’t the gating factor — where communities want the investment, where rails and ports are already in place — and we, as buyers, accept a premium for cleaner processing technology — as the price of doing it here in the U.S., and shoring up our supply chains, we might find that pyrrhic permitting victories were fights we never needed to pick.

Let’s turn a regulatory problem into a logistics problem. Logistics problems have solutions.

Agree? Disagree? Something I missed? Write in to me here with what you think. Would love to hear from you.