In September 2022, Dan Goldin received the inaugural Tech Freedom Award from the Krach Institute for Tech Diplomacy at Purdue.

This is his acceptance speech — beginning with his memories of being born as World War II broke out, living through the war as a small child, and understanding both the terror that consumed his relatives who never made it out of Hitler’s Europe and the technological breakthroughs that ultimately secured America’s — and much of the free world’s — freedom.

The audio quality isn’t great (Team Goldin was still getting its media legs then!), but it feels important to share this moment with you all. If it resonates, let us know at team@peraspera.us.

Dan Goldin serves on the Advisory Council for the Krach Institute for Tech Diplomacy at Purdue.

Full video

Full transcript

Keith Krach. On behalf of this great nation, the Institute for Tech Diplomacy at Purdue, everyone assembled here in this room and space lovers around the world, we salute you, we love you and we honor you.

Dan Goldin. We’re going to have a little show and tell, and I’m going to take you through history.

I have lived over eight decades. I was born just when World War Two started, and I lived through World War Two. On this chart, here is the march of technology and the people who made that technology happen. And this is why we have such an incredible economy in America, and this is why we’ve maintained our freedom.

The story begins with my father, who graduated college during the Depression and had very little. But he had values that he gave me. He had visions and dreams, and he drove me to unbelievable limits, and I got damn frustrated with him, but he was very, very instrumental in my life.

The world was not a pretty place between 1939 and 1945 and totalitarianism broke out, and it was only because of the technological advancement that we had in America that we made it through the horrors of World War Two. When It ended, as a child, I remembered the happiness in the street and the belief that there was going to be no more war.

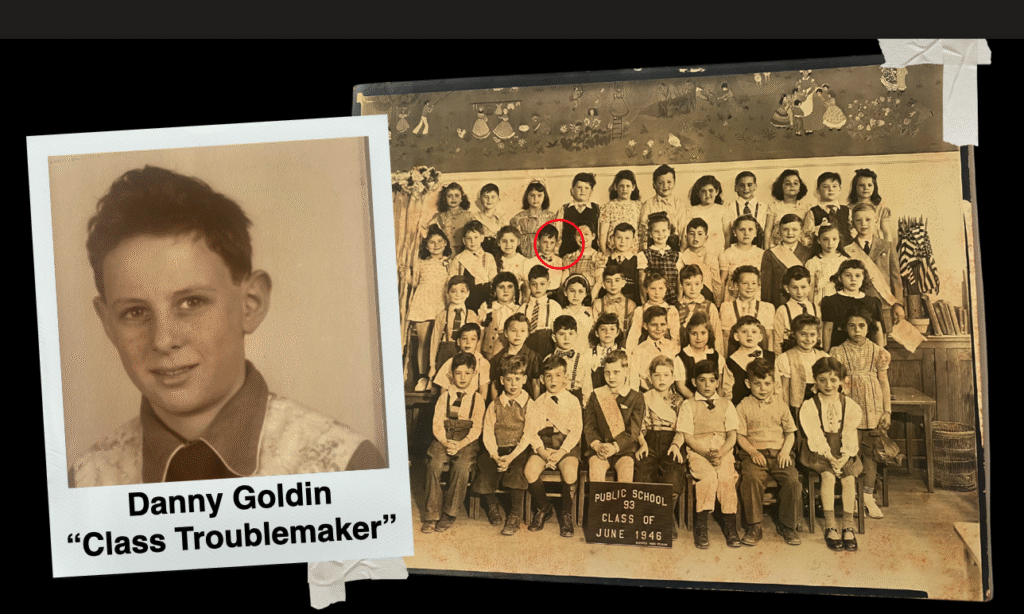

This is my first-grade class at PS 93. This was 1946. By the sixth grade in 1952,

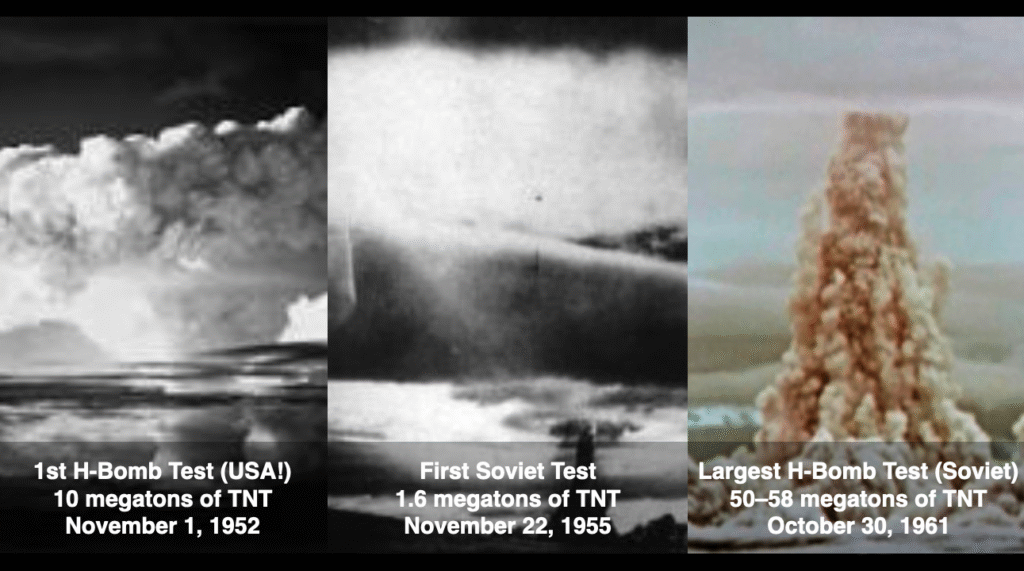

that happiness faded, because we were doing duck-and-cover dives in case of an atomic bomb attack. In November 1961, the Russians exploded the largest hydrogen bomb ever — 50 to 58 megatons. It was horrifying.

Living at that time, America had to develop technology. It was not easy technology. And then came Sputnik. The World at first got amazed. I was in Physics 101 as a freshman, and my professor, Donald Cotton, said, “Sputnik is watching you”. He heard it on a news station during the during lunch — not on CNN, and I’m going to play for you the meaning of Sputnik from a General Kenny who was introduced on the news in 1957:

“What is the significance of the Soviet satellite? Why should we worry about the fact that the Soviet Union has beaten us by a few months in launching a satellite — a Sputnik — that goes around the world? The weapon we are all working toward — both us and the Russians — is the intercontinental ballistic missile. And the job in making an intercontinental ballistic missile is to get enough power behind that package so that you can drive it across the ocean. If you can shove this satellite up 560 miles, you have enough power behind that thing to drive it across the ocean.”

It was chilling. America was not advancing technology; we were ignoring it. And it took a new young president to understand that launching rockets is fun, but the implication of an intercontinental ballistic missile with a hydrogen bomb on top was far more serious. And I’m intentionally talking this way because this is the life I lived. I’m not trying to scare; I want to deal with the reality of what we live in today.

President Kennedy said, “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy but because they are hard.” And I said, “No graduate school — I’m going straight to NASA.”

That is my wife, whom I dragged out of New York City to big, bad Cleveland, Ohio. She’s been with me for six decades. We were married 60 years on June 9.

At NASA Lewis, I worked on a mass spectrometer. Little did I know — let me step back — little did I know that five decades later I’d be working with a Nobel Prize winner to understand the origins of the universe, and actually capture antimatter on the AMS payload on the International Space Station. Sam Ting and I still collaborate on this. It’s getting very close. Sam will report — I helped Sam.

But you cannot go through life focused only on science and technology. When a quarter of my family was wiped out in World War Two, I learned you cannot remain silent. So in 1964, I read that the Soviet Union was suppressing religious freedom, locking people up, and committing terrible acts. I formed an organization with five of my friends. We took on the Soviet Union. We fought in Congress. We communicated around the world. And in 1975, the Jackson-Vanik Amendment was passed, and a million Jews were let out of Russia. Other religious groups were also freed.

Oops — I’m having a little trouble here. I could design the telescope, but I can’t operate this damn thing.

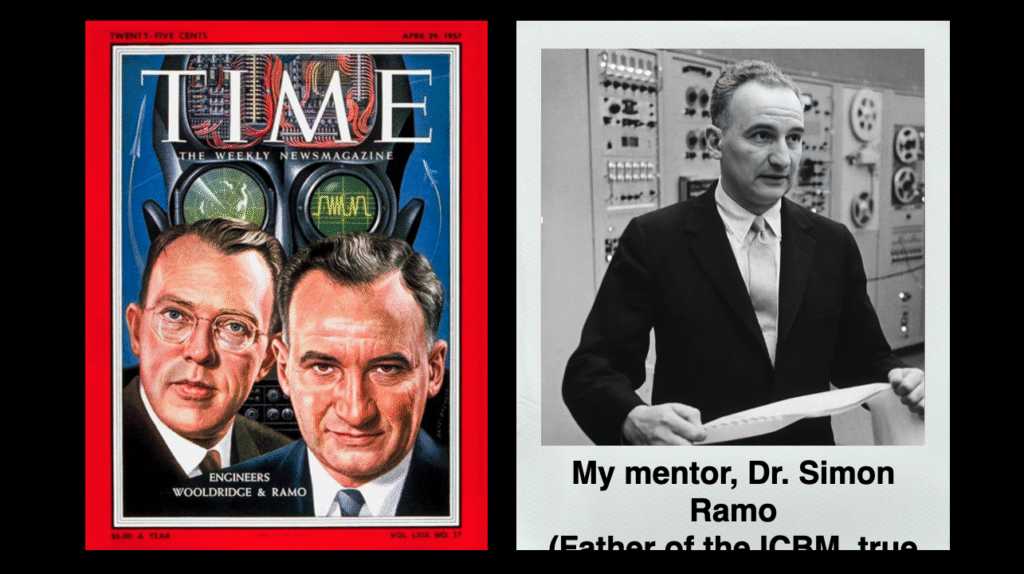

My tenure at NASA was done in five years when I got a call from Si Ramo, Dr. Ramo at TRW, because America needed to work on defending us from the terrors of intercontinental ballistic missiles. And Judy was kind enough — and our two daughters — off we went to Los Angeles.

I got the privilege of working for Dr. Simon Ramo, the man President Eisenhower asked to build an intercontinental ballistic missile when America did not pay attention and focus on the technologies that would keep our nation safe.

This man was my mentor until he was 103. In 2016 he passed away. I had lunch with him every quarter — and he beat me up all the time.

There it is. There are many things I did at TRW that I cannot talk about, but I can say I led each one of these activities:

• How to detect Russian ballistic missiles the minute they take off, so that the President of the United States and the President of Russia could talk and prevent an apocalypse — that’s called Mutually Assured Destruction

• I oversaw America’s land-based missiles.

• President Reagan, working with Edward Teller, wanted directed-energy weapons to stop, at the speed of light, ballistic missiles from ever hitting America. I worked directly with Dr. Edward Teller, and we did Brilliant Pebbles and Brilliant Eyes.

• And finally, I worked on the Milstar secure worldwide communications payload, and I had the honor of leading the design and engineering of it.

I worked on other things I can’t talk about — technology that allowed people to sleep in their beds at night and not feel threatened.

That’s it.

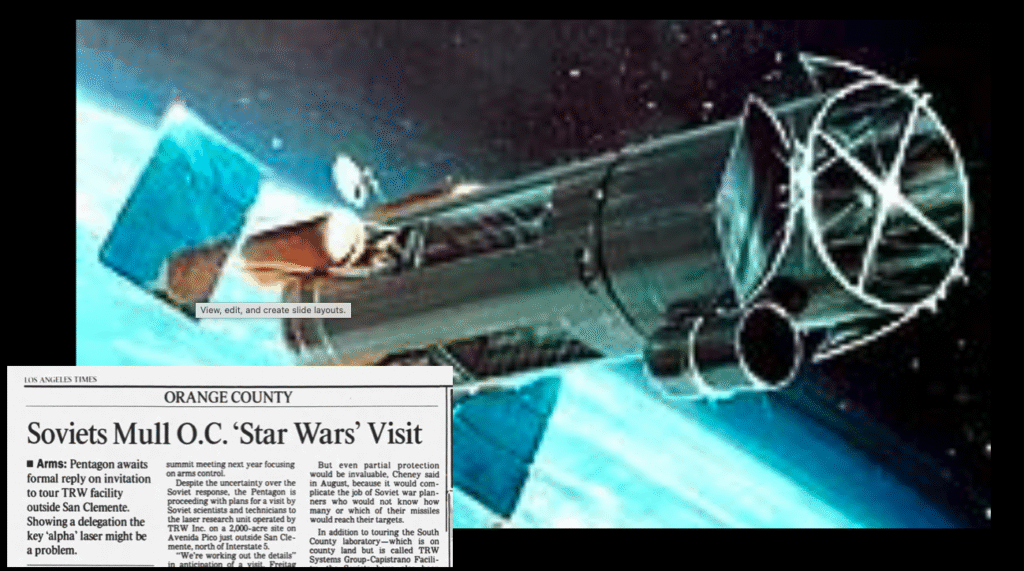

This is the Alpha laser. It’s a directed-energy weapon. And just before George H. W. Bush met with Mikhail Gorbachev to discuss peace, he asked a group of Russian generals and scientists to come to America and come to the directed-energy lab that I oversaw. That’s the device. Whoops, they actually announced it in the paper.

And next — some months later — the Berlin Wall came down, and Mikhail Gorbachev resigned, and a new level of peace broke out because of strength in American technology, and people could sleep at night.

Two months after the Cold War ended, I got a call to work for George H. W. Bush and help him get NASA back on track. NASA wasn’t bad, but the Cold War was over, and you can’t have a Cold War space program. You need one that’s open, that drives technology, and that doesn’t look backwards.

And the first thing President Bush said to me as we sat — I couldn’t believe it, here I am sitting in the Oval Office with the President of the United States; it’s unbelievable — I grew up on Boynton Avenue, for God’s sake, and Keith over here grew up on Elder Avenue. We went to kindergarten together.

In any case, President Bush said, “I understand what happened at Versailles. We didn’t pay attention to Germany at the end of World War One. That’s not going to happen now. And we’re going to ask the Russians if we can bring the U.S. Space Shuttle to their Mir space station.”

And within a few days, I was meeting with Boris Yeltsin to make it happen.

Then I went to work for Bill Clinton, who said we were going to continue this, because we wanted our planet to be peaceful. And he wanted me to ask the Russians — and 15 other countries — to join us and build the International Space Station as a symbol of peace, as a symbol of technology, to tell everyone the Cold War is over.

He made me debate his Cabinet first to prove I could take the heat, and then he asked me to do it. And then George W. Bush, who believed deeply in science and supported many of the science programs we started late in my tenure — he also supported safety in space, and to that I’m very appreciative. We talked about the Shuttle — I prayed 61 times. One in 72 is the probability of failure. It was scary. Judy saved me from me and said, “Not 62. You’re coming home.”

Oops.

John Glenn flew two weeks after I started working at NASA. He helped America regain its momentum in space. He was an American hero. And later, when he walked into my office at 76 years old, he said, “You’re going to send me back to space.” John F. Kennedy, when Glenn landed on Friendship 7, called him on the aircraft carrier and said, “You’re never going back to space again. You’re an American hero and we can’t afford to lose you.”

Well, now Senator Glenn looked at me and said, “Dan, you’re going to send me.”

I said, “No, I’m not.”

And then he said, “You’re gonna.”

So I’m talking to a U.S. Senator — my hero — and I said, “You’re going to have to get Annie to call me and tell me she accepts that you could die in space. You’re going to have to resign from the U.S. Senate permanently. And you’re going to have to get the Nobel Prize winner who runs the National Institutes of Health to call me and say you’re doing meritorious science. Because I’m not sending a Shuttle up with someone who’s going to play patty-cake.”

I went home and said to Judy, “He’s never going back to space.” She laughed. And he did every single thing he said he would do. I sent him to space. He came back safely. And he was as strong and as sharp as people a third his age. An amazing man, and I was honored to work and be with.

Now, we throw around this word — the International Space Station — and I don’t think anyone has a real appreciation for what it is. It looks like it’s out of Star Wars. It’s 357 feet across. There’s a robot that goes back and forth on a train track. There’s pressurized space equivalent to a giant 747. It produces 100 kilowatts of electricity. It weighs almost a million pounds. It took 42 Shuttle flights. And it’s up in space — and America and the world pretend it’s just… there. Just something that gets done.

But on that station, we are learning how people can live and work in space. Because when you go to space, you get osteoporosis, your bones dissolve, your muscles atrophy, your whole DNA gets rewritten. And we will never be able to be a spacefaring nation and planet without understanding this. This is the place where it will happen. And I am so proud of our nation because we led the Russians and 15 other nations to build it. And even though tensions are high right now between Russia and America — and the West and the East — everybody is still working together. And when people work together, it’s good.

When I got to NASA, I asked, “Where is the hypersonics program?”

There was none.

There was a program — which was a figment of everyone’s imagination — called the National Aerospace Plane. The Orient Express. The promise of a plane that would take you from San Francisco to Tokyo in three hours.

I went to the President, and we canceled the damn thing. And I asked the NASA team — and Mark Lewis, standing right there — a brilliant young professor at the time — along with half a dozen others, to make that plane actually happen.

And it did.

It became the only air-breathing scramjet hypersonic vehicle. It flew. It traveled — actually, Keith, 9.6 Mach — but who’s counting? And it happened three years after I left. It wasn’t $3 billion. It wasn’t $10 billion. It was $300 million. And America had the lead. And again, we forgot about technical excellence. We got busy building the weapons of the past instead of having the courage to build the weapons of the future. NASA did it with brilliant people like Mark Lewis.

You I’m almost done. Please stick with me. I’m a little crazy.

My father took me to the Museum of Natural History — the Hayden Planetarium on the west side of Central Park — when I was seven years old. He wanted me to understand science. He walked me through that place, and I knew at that moment that astrophysics was going to be what I did. I read textbooks. I went to the library. I did research. I even fired rocket engines in my friend Marty Heidelberg’s bathtub, and his mother got really upset.

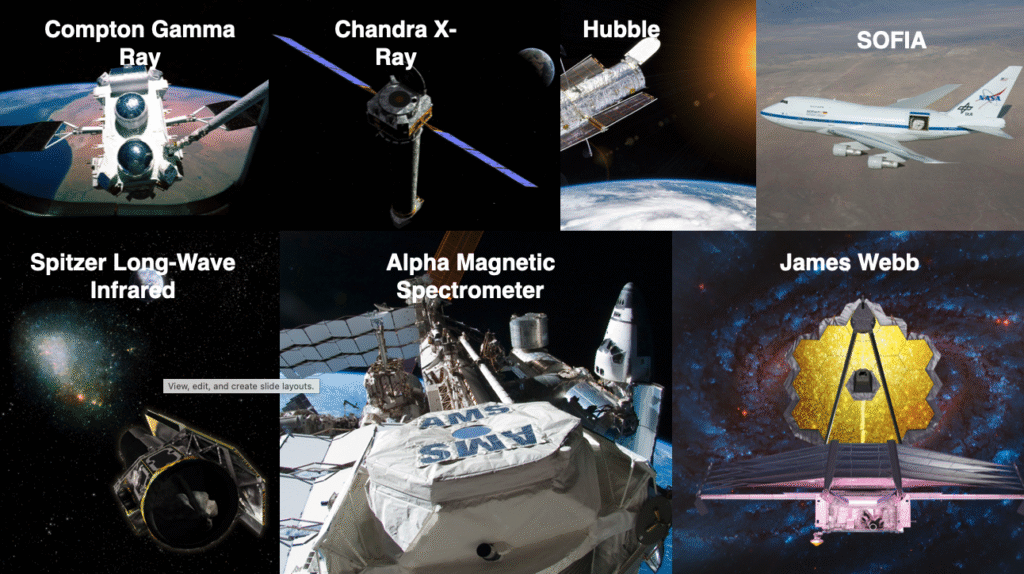

But when I was at TRW — which is now Northrop Grumman — working for Dr. Ramo, I led the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, which looked for extremely energetic events in the heavens. And I oversaw the Chandra X-ray Telescope. And when the U.S. Congress was preparing to cancel the program — even though I was running a multibillion-dollar business — I volunteered to make sure we could grind the X-ray incidence mirrors. And we did. I went to NASA, we built it, and it’s still working.

And I’m telling you this not about me, but because this is what our country does when we’re not afraid to take high risks — when we don’t back off and we press forward.

When I got to NASA, the Congress was ready to write off the Hubble Space Telescope. We’d spent $5 billion; it was dying on orbit.

We put together a team led by Randy Brinkley — who couldn’t be here tonight. He was a fighter-pilot — an F-18 pilot. He didn’t understand how electrons go around protons, but he knew people. Randy Brinkley led the team that fixed the Hubble Telescope in December of 1993, and it’s still operating today.

Spitzer infrared telescope and AMS. It’s still working today on the International Space Station.

And the NASA people in the Science Directorate wanted nothing to do with AMS because it came from the Department of Energy. That’s how our government works. So I mandated that we build AMS, and I asked the astronauts at NASA Johnson to do it. They worked with Sam Ting, and it’s still operating today, and the results are coming back really good.

We’re almost done.

The James Webb — I had to wrestle the National Academy of Sciences to the ground because they didn’t have the backbone and courage to make it big enough and cold enough. But the brilliant team at NASA — John Mather, NASA’s Nobel laureate — led it, along with the team at Northrop Grumman, my old team at TRW. Everyone said it couldn’t be done. It was too hard. 383 impossible things. But we did it.

And we are now peering back to the very beginnings of creation — and they’re just getting started.

But you can’t just do science. What we started at NASA was the Origins Program. When I met with George H. W. Bush, we wanted to understand the origin, evolution, and destiny of the universe — and life within it. And if you just make it a science task, it’s not enough.

So I decided to meet with the world’s leaders — religious leaders. And I had the opportunity to meet with Pope John Paul II. There you see me with a montage explaining to him the signs of life.

And I’d like to tell you — most of you don’t know this — that in interstellar space, there are hundreds of complex hydrocarbons, the very building blocks of life. I believe life exists somewhere in the universe, but it’s not little green men chasing F-18s like you read in the news.

America is an amazing country. And the President doesn’t just rule the country — there’s a Congress of Republicans and Democrats. It’s America’s space program.

I worked with these wonderful people. I used young pictures of them so they look good. Amazing.

The man who saved the Space Station — the vote was 215 to 215. Jeff Lawrence is out here. He was head of Legislative Affairs at NASA. He threw me in front of John Lewis at nine or ten o’clock at night and said, “Ask him to vote for the Space Station.”

I literally jumped in his path, and he broke out laughing. And I said, “Congressman Lewis, the future of America’s space program depends on you.” He was rolling on the floor.

Then he looked at me, and I said, “How are you going to vote?”

“I ain’t telling you.”

I was down to my knuckles on my fingers — and he went in and voted for America’s space program: 216 to 215.

One vote.

I’d like to play a video now — can you play, I think, the second video?

The first half of the 20th century was — this is Rich at Chautauqua — was scientific discovery in physics.

The second half of the 20th century — although great things happened in physics — was dominated by biology. Many of us are alive today because of what happened in biology in the second half of the 20th century. Our children will live even longer because of that.

But the first half of the 21st century is going to bring something new and different. And that is the intersection of biology and physics. We are going to start mimicking the behavior of the minds of living things — the sensory systems of living things — and bring them together to build a richer economy and stronger tools, and help those that need them.

This was 2010. It’s going to happen. Change is coming.

But America sat on its knuckles for the last decade. We outsourced our manufacturing around the world. We don’t build semiconductors here. We’re not building neurobiologically based devices here.

Here we have something in America called Design affair of. What is it? Fabulous manufacturing. It’s a polite term to say that America doesn’t have to spend the capex. America doesn’t have to spend the risk in the OPEX to build these new devices.

What America does is go to every country around the world and have them build it for us.

And that didn’t work too well after COVID, because we have a global supply chain problem. We can’t even build automobiles anymore. This is the number one problem for America.

We’ve made a small step forward with the CHIPS Act. I sent Keith Krach an email when he was Under Secretary of State, and I said America needs to spend a trillion dollars, and I gave him a plan to do it.

Congress — and both Republican and Democratic administrations — haven’t had the courage to do this. Because if we don’t do this, we’re not going to have an economy. And if we don’t have an economy, we’re going to go to a very bad place. And this is the reason I spent this time talking about all of this. Because I really believe it.

And what you see there is the new patch panel — General Edelman and I got together days after I left NASA to work with Gerald Edelman, a Nobel Prize winner. And I said, “Gerald, you and I are going to build an autonomous vehicle. Not one that follows instructions — but one we train.”

We built a robot. We trained it to play soccer, and we beat Carnegie Mellon 24 to 3. I then built that chip, but I couldn’t get the funding necessary, because America didn’t believe in foundries in America, and my company ran out of business, but that chip is better than almost any chip that exists right now, and I’m proud of it.

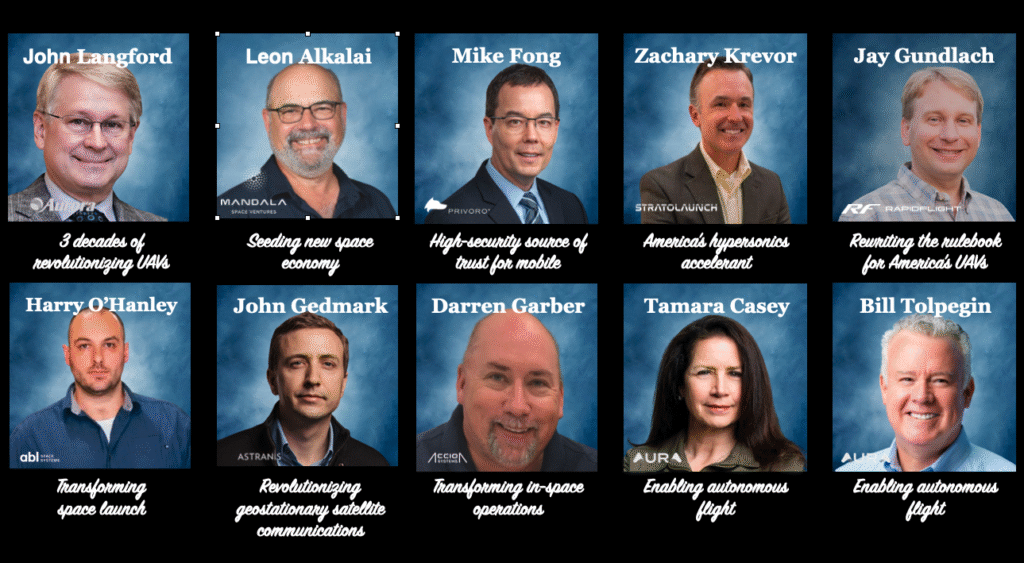

At this point, all I’m going to do is flash through wonderful people who, in the last few years, I’ve been mentoring. I retired — and then I met a crazy guy named Steve Feinberg. And now I’m working 10 hours a day, seven days a week, helping build the economy I’m talking about.

And Jake — are you here? This young man is going to build the greatest UAVs on the planet.

He’s going to transform aviation tomorrow. Casey is here. Bill topagan is here. Darren Garber is here. I’m so proud of these people, I drive them crazy. I’m not in charge, but they’re going to change America. I’m going to end by playing the last video, and I’ll tell you what it’s about afterwards.

A week.

These crazy people, at my insistence, in 1993 — I challenged them to cut the cost of going to Mars by an order of magnitude, and I challenged them to do it in 1/3 the time, 300 million in three years. And I didn’t want them to just land on Mars. I wanted them to deploy a robot that traveled all over Mars.

And they did it. That’s what success looks like. That’s what America looks like, and that’s what everyone in this room should do. Thank you so much.